The Tribune of the People versus the Radical Congress - Part 1 of 3

On February 24, 1868, led by Radical Republicans Thaddeus Stevens, Benjamin Butler, and John Bingham, the U. S. House of Representatives voted 126 to 47 to impeach President Andrew Johnson. It may be astonishing to those who consider partisan propaganda truthful history, but the nature of the Democrat and Republican parties has changed immensely since 1868. Democrat was almost a synonym for conservative then, while the Mercantilist leanings of the Republican Party of the time are increasingly being displaced by conservative and populist values.

Is this history relevant to Radical Democrat talk of impeaching President Donald Trump today?

Yes, there is a general parallel, but I will let the reader discern it step by step for now.

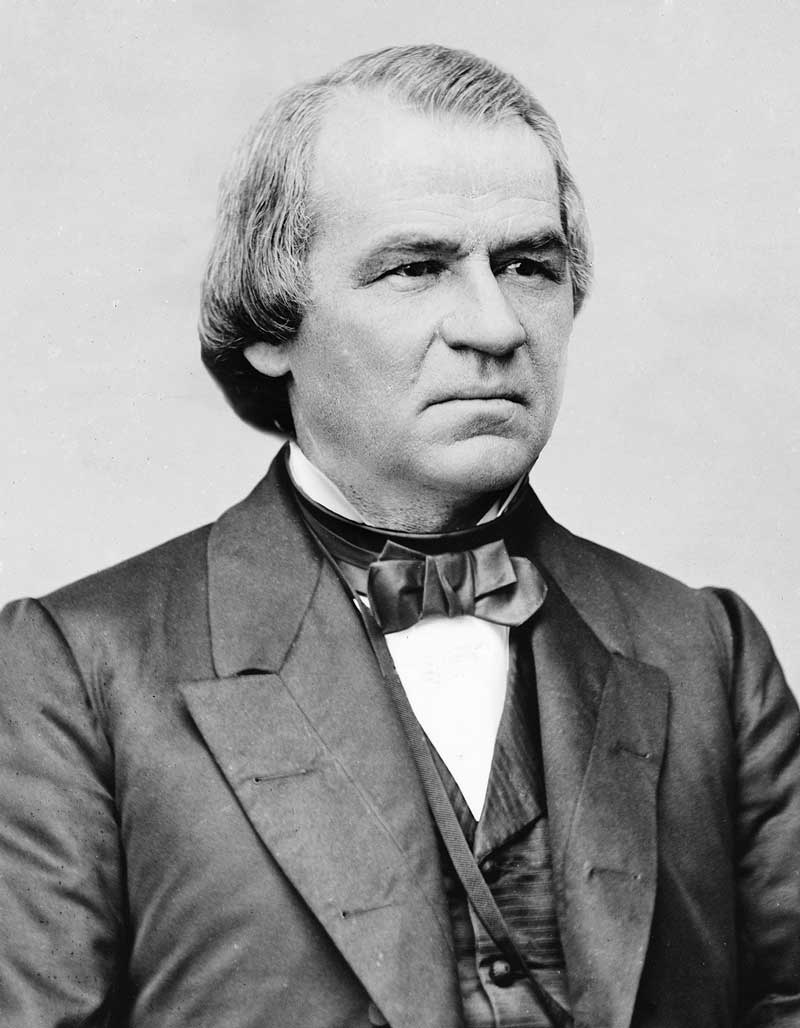

President Lincoln chose Andrew Johnson, the Union Military Governor of Tennessee, to be his Vice Presidential running mate on the “National Unity” or Union-Republican ticket in 1864 in hopes of garnering the votes of pro-war Democrats in the November election. Johnson had been a Democratic Senator from Tennessee, but he refused to side with his state when Tennessee seceded in 1861. Politically he was a Jacksonian conservative. He believed strongly in States Rights and limited constitutional government, but just as strongly rejected the concepts of state secession and nullification. In Tennessee politics he had identified himself with the interests of the common people and against the interests of the wealthy planter classes. Like most Democrats and conservative Northern Republicans he supported the constitutionality of slavery. Although his political beliefs were very close to other Southern Democrats except for secession, he was known for his severe and threatening criticisms of secessionists.

Because of Johnson’s harsh and sometimes vengeful remarks about secessionists, the Radical Republicans assumed he would support their radical aims for reconstructing the South after the war. The Radical Republicans were very uneasy about Lincoln’s March 4, 1865 inauguration speech in which he indicated a lenient plan for reconstructing the South. Lincoln believed that a magnanimous policy on reconstruction would avoid further regional conflict and pave the way for rebuilding political alliances between Northern Republicans and Southern business interests. The Radicals, however, probably judged rightly that Southern politicians would not support the Whig-Republican policies of high protective tariffs and government subsidies for industry or a national bank (essentially fiat money). They believed that welcoming Southern States back into the Union without radically restructuring Southern society would only result in more Democrats in Congress, thus threatening continued Radical Republican dominance and control. The Radicals believed the South deserved to be severely punished and exploited and made into Republican states before reentering the Union. The latter objective was to be achieved by enfranchising black voters and disenfranching Confederate veterans, thus giving the Radicals permanent political dominance in the South and thereby the nation.

When the Radicals realized that Johnson intended to follow the same lenient Reconstruction policies as Lincoln, they began to oppose him strongly and plot how they might limit his power and influence. The first confrontation between the Radicals and Johnson began when the Radical dominated Congress refused to seat the new Southern delegates elected in 1865. This left them free to impose their punitive policies on the South. Their excuse was that Southern states were trying to circumvent the abolition of slavery, instituting “black codes” to limit the civil rights of blacks, and failing to control racial violence. There was little truth to these excuses, but campaigning against the faults of the South was a successful political strategy in the North. Johnson pointed out the hypocrisy of Northern legislators, whose states (for example: Indiana, Illinois, Ohio, and Oregon), had far more restrictive “black laws” than any in the South. Yet they were using the issue as an excuse to impose punitive measures on the South.

In February of 1866, Johnson successfully vetoed the first Freedman’s Bureau Bill. This bill would have extended many civil rights to the newly freed blacks, but also authorized confiscation of land from whites for redistribution to blacks, established previously unheard of social-welfare programs for blacks but not for whites, and established an extra-constitutional military tribunal system for whites accused of violating the rights of blacks. Johnson noted in his veto message that:

“A system for the support of indigent persons in the United States was never contemplated by the authors of the Constitution; nor can any good reason be advanced why, as a permanent establishment, it should be founded on one class or color of our people more than another…The idea on which the slaves were assisted to freedom was that on becoming free they would be a self-sustaining population. Any legislation that shall imply that they are not expected to attain a self-sustaining condition must have a tendency injurious alike to their character and their prospects.”

Congress later passed a modified and only slightly less heinous version of the Freedman’s Bill in February 1867 and was then able to override Johnson’s veto.

In March 1866, Congress passed the Civil Rights Act of 1866. This bill duplicated many civil rights laws already passed by the states, but its real intent as seen by Johnson was to grant the federal government unlimited power to intervene in state affairs. It also granted revolutionary police powers to Freedman’s Bureau officials to enforce all civil rights laws. Johnson feared it was so severe that it might resuscitate armed rebellion. Congress overrode Johnson’s veto. Several provisions of this Act were later incorporated into the Fourteenth Amendment, which Johnson strongly opposed, rightly predicting that it would lead to a consolidation of power at the federal level—in effect turning the Constitution upside down.

In May 1866, there was a race riot in Memphis. The conflict was between black Union soldiers and white Irish Police of recent Northern origin, but the Radicals made good use of it as an example of Southern intolerance and violence.

By early summer 1866, the new state government in Louisiana had elected state legislators, state executive officers, and a Mayor for New Orleans. Much to the displeasure of the Radical Republicans, Louisiana was returning to Democratic Party control, and it was only a matter of time before a Democratic Governor might also be elected. The Republicans immediately laid plans for overturning the newly elected government. They called for a reconvening of the 1864 Union Military Government appointed convention to amend the state constitution and hold new elections. Only those eligible to vote in 1864 (mainly Radical Republicans) would be allowed to vote for delegates. The plan was to void the recent Democratic electoral victory, disenfranchise most Confederate veterans, and enfranchise blacks, thus establishing a sizable Republican political dominance.

Hearing of this revolutionary attempt to overthrow the legally-elected government of Louisiana, President Johnson demanded that the Radical Republican Governor, Madison Wells, halt this proceeding. Wells ignored the President and continued to pursue plans to displace the recently elected conservatives and establish a lasting Republican dominance. Outraged at this, Mayor Monroe of New Orleans and the Lieutenant-Governor Voorhies called for Union General Baird, commanding federal forces in the city, to prevent the illegal Radical convention from taking place. Baird declined to interfere and only offered to protect the convention and the city from mob action.

On the Friday before the Monday, July 30, 1866, convention, the Radicals organized a mass meeting denouncing Johnson and urging blacks to arm themselves to protect their rights and any attempts by New Orleans authorities to break up the convention. A white radical threatened that “the streets will run with blood,” if there is any interference with the convention, and urged the mainly black gathering of several thousand to come in force on Monday.

Alarmed at this, General Baird telegraphed the President for instructions. All telegraphs to the President, however, came through the War Department and Secretary of War Edwin Stanton.

On Monday, as incited by the radicals, a variously armed and intoxicated mob of freedmen swarmed the convention and came in conflict with Democratic protestors and New Orleans Police. About fifty people were killed in the ensuing riot and mayhem, most of them blacks. General Baird’s Federal troops arrived after the fact.

President Johnson’s telegram from General Baird was not received until the riot was over. Secretary Stanton, with no explanation, had deliberately withheld it from him. As news of the bloody riot was received in the North, the Radical Republicans and their allies in the press and pulpit exploded with inflammatory denunciations of the South and Johnson’s lenient Reconstruction policies. By this time, President Johnson was thoroughly disenchanted with Stanton.