The Hammer of Evil Falls Short – Part 3

On February 24, 1868, the U.S. House, led by Radical Republicans Thaddeus Stevens, Benjamin Butler, and John Bingham approved an impeachment resolution against President Andrew Johnson by a vote of 126 to 47. There were eleven articles of impeachment, but a central issue was that Johnson had violated the Tenure of Office Act Congress passed in March 1867 to protect Radical Republican Secretary of War Edmund Stanton from being fired by President Johnson. Johnson’s veto of the bill was overridden in the Senate.

A stronger central issue was that Johnson was opposed to many of the political objectives of the Radical Republicans, especially regarding their Reconstruction policies, many of which were harshly punitive and exploitive to Southern States. He had also traveled the country campaigning against the Radical Republican Reconstruction policies. The ultimate Radical objective was to make the South into a means of establishing permanent Radical Republican dominance.

Johnson had been displeased with Stanton’s ethical conduct and duplicity on several accounts, but the final straw was the discovery in early August 1867 that Stanton had deliberately suppressed and concealed from him a petition for mercy for Mary Surratt in the Military Commission Trial of Lincoln assassination conspirators. Stanton had also withheld exculpatory evidence in the trial. Marry Surratt was hanged on July 7, 1865, in what has to be one of the most grievous injustices in American history. Johnson knew that firing Stanton would result in a Congressional attempt to impeach him but felt that truth and honor left him no recourse. Stanton, however, refused to vacate the office.

A two-thirds Senate majority was necessary for conviction. Acting as presiding officer and judge was Chief Justice Solomon Chase, a Radical Republican, who had been Lincoln’s Treasury Secretary. The Senate floor leaders for conviction were Ohio Senator Benjamin Wade and Massachusetts Senator Charles Sumner, the acknowledged leaders of Radical Republicans in the Senate. Johnson was defended by Henry Stanbery, who temporarily resigned his position as Attorney General to defend his president.

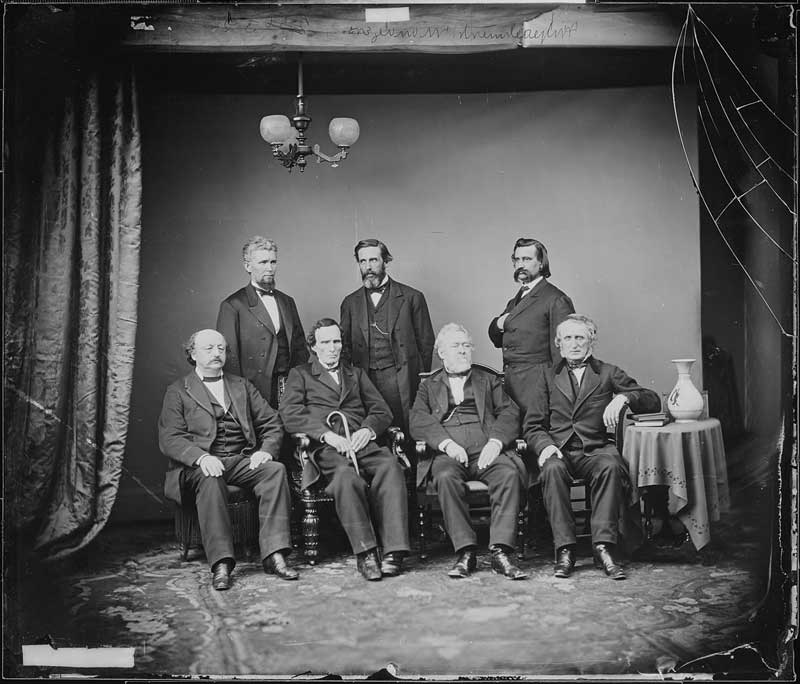

Some background on the Radical Republicans and their attempts to establish a permanent dominance in Congress and over the States should be helpful in understanding their attempt to remove President Johnson. Five men exercised dominant leadership of the Radical Republicans: Thaddeus Stevens, Representative from Pennsylvania; Benjamin Butler, Representative from Massachusetts; Charles Sumner, Senator from Massachusetts; Benjamin Wade, Senator from Ohio; and Secretary of War, Edwin Stanton. Stanton had gained the respect of the Radical Republicans during the War because of his forceful advocacy of Total War Policy against Southern civilians and the Southern economy as well as Confederate military operations. As Senate Leader, Ben Wade would become President, if Johnson were removed.

A principal goal of the Radical Republicans was to pass the Fourteenth Amendment, which although containing some worthwhile civil rights provisions, would have outlawed former Confederate leaders from holding public office and also essentially turn the Constitution upside down by giving Congress unprecedented power over the States.

An indication of Radical Republican political ruthlessness was seen when The 39th Congress convened in December of 1865 just as the states, including seven Southern states, were finalizing ratification of the Thirteenth Amendment abolishing slavery. The Radical Republicans knew that they could not depend on elected Southern Congressmen to achieve the two-thirds super majorities in the U. S. Senate and House to pass the Fourteenth Amendment. Consequently, they mustered a majority in both Houses of Congress and voted not to seat the 22 Senators and 58 representatives from eleven formerly Confederate Southern States.

Tennessee was the first to ratify the amendment, but without a proper quorum of its legislature. Nevertheless, despite this irregularity, Tennessee was counted for ratification. By February 6, 1867, all ten of the remaining Southern states and three Border States had rejected the amendment

The Radical Republicans, however, had a radical plan to reverse Southern rejections of the Fourteenth Amendment that fit their longer range agenda. Under their leadership on March 2, 1867, a Reconstruction Act was passed over the veto of President Johnson that revoked the legal status of the ten Southern states that had rejected the Fourteenth Amendment and placed them under a military government administered through five U. S. Army districts. They would not be readmitted to the Union unless they passed the Fourteenth Amendment. The Act also disenfranchised Confederate veterans. The Fourteenth Amendment was eventually passed on July 9, 1868 but without the President’s signature and in violation of Articles I, IV, and V of the Constitution. It never received a legitimate lawful vote of three-quarters of the States. The sordid ethical details are contained in Chapter 20 of my book, The Un-Civil War: Shattering the Historical Myths. With ten Southern States denied representation in the Senate, the very composition of the Senate during President Johnson’s impeachment trial was illegitimately stacked against him.

The opening argument for impeachment trial in the Senate was made by House impeachment manager, Benjamin Butler. The closing argument for impeachment was made by Thaddeus Stevens, and the closing argument for defense by Attorney General Henry Stanbery. Thirty-six votes were required for the two-thirds necessary for conviction. On May 16, the House managers brought up Article XI regarding the President’s speeches against the effort of Radical Republicans to impose outrageously harsh Reconstruction terms on the South. The vote was 35 for conviction and 19 against, one vote short of conviction. On May 26, the Senate failed to convict Johnson on Articles II and III by the same vote and abandoned further attempts at conviction. Of the 19 votes against conviction, ten were courageous Republicans rebuking Radical Republican leadership. All nine Democrats in the Senate voted against conviction. President Johnson was acquitted, and the Radical Republicans’ dubious attempt to remove him from office based on policy disagreements was frustrated. The Senate, however, retaliated against Henry Stanbery by shamelessly refusing to re-confirm him as Attorney General.

Perhaps the best summary of the Presidency of Andrew Johnson and his conflict with Stanton and the Radical Republicans came from Gideon Welles, Secretary of the Navy under both Lincoln and Johnson:

“The real and true cause of assault and persecution was the fearless and unswerving fidelity of the president to the Constitution, his opposition to central Congressional usurpation, and his maintenance of the rights of the states and of the Executive Department against legislative aggression…carried on by a fragment of Congress that arrogated to itself authority to exclude States and people from their constitutional right of representation, against an Executive striving under infinite embarrassments to preserve State, Federal and Popular Rights.”

Secretary of War Edwin Stanton’s star began to fall with Johnson’s acquittal. The revelations of his conduct during the Lincoln assassination conspiracy trials and especially that relating to the hanging of Mary Surratt no doubt figured in his failure to achieve his ambition to become President. Ulysses S. Grant was the successful nominee of the Republican Party in 1868. Grant nominated Stanton to be Ambassador to Mexico, but he declined it. After much persuasion by Congressional Republicans, the wary Grant finally nominated Stanton to a Supreme Court vacancy on his 55th birthday, December 19, 1869. He was immediately approved by the Senate, but Grant delayed in making the appointment.

On December 23 of 1869, Stanton requested his old confidant, Col. Wood, to visit him and explain why Grant was delaying his appointment to the Court. Wood informed him of his opinion—which he never disclosed publicly. Stanton then lamented that “the Surratt woman haunts me so that my nights are sleepless and my days are miserable.” He added that he wished that Wood had tried harder to stop her execution, though he admitted that he was personally responsible for blocking Wood’s efforts. Early in the morning the next day, December 24, 1869, Edwin Stanton died at his home.

Thus the hammer of evil fell short of removing President Andrew Johnson from office on the basis of policy differences and violation of the contrived Tenure of Office Act, which was later ruled unconstitutional. But many of the wounds inflicted on the country by Radical Republican policies and tactics—including inciting racial tensions-- are still with us. Their hammer has been passed to Radical Democrats contriving to impeach President Trump and destroy the foundations of American freedom and culture.