Reconstructing Truth in a Hurricane of Propaganda

Part 4 of a Series on Confederate Cavalry

During the morning of April 12, 1864, Forrest had made a reconnaissance of the outer perimeter of earthworks at Fort Pillow. He had found that all but the inner fort was vulnerable to sniper fire from higher terrain. He doubled the line of sharpshooters already placed there by General Chalmers. He was, however, painfully injured falling from his horse, which was shot from under him.

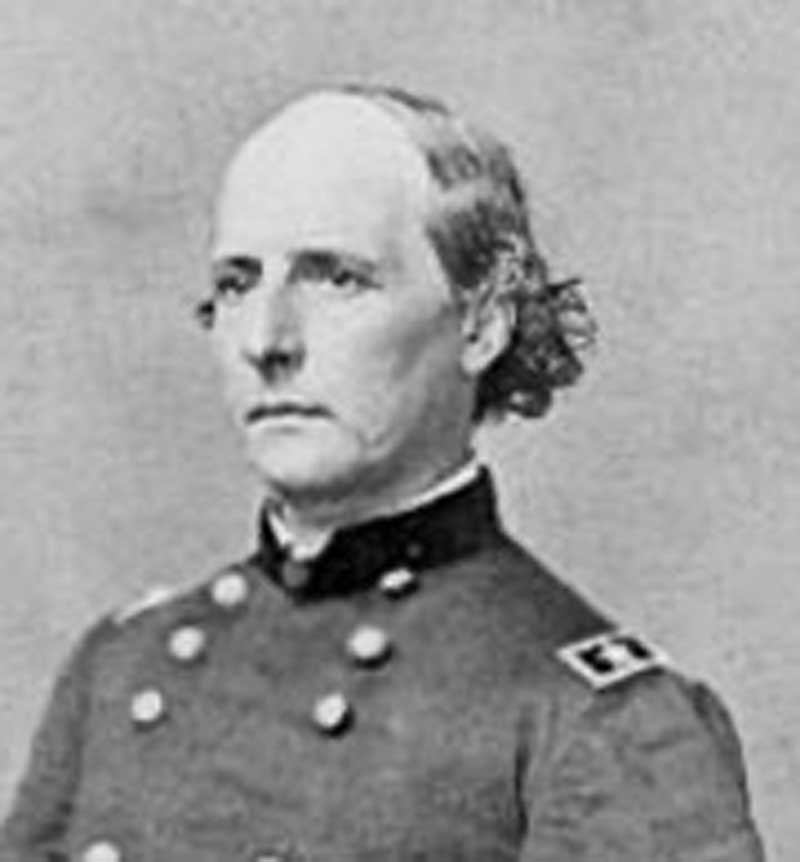

Suppressing potentially deadly Union artillery fire against the assembling Confederate assault was obviously a priority. The 9 white officers and 253 black artillery men of the Sixth U.S. Colored Troops Heavy Artillery Battalion and D Company of the Second U.S. Colored Troops Light Artillery Battalion were thus a natural and important target for the Confederate sharpshooters situated on higher terrain. Indeed, the Union artillery commander, Major Lionel Booth, was killed about 9 AM.

The two Union artillery units had only been formed about one month before in Mississippi and consisted of Mississippi and West Tennessee recruits and conscripts. The typical Union artillery battery had 18 to 30 heavy guns. Fort Pillow only had six light artillery pieces. Few if any of the enlisted men could have had much training or experience. Many had been issued rifles, but some were armed only with clubs. They probably acted both as a security force and as labor for the 14 cotton dealers involved in the Memphis Union Commander Stephen Hurlbut’s cotton-ring for war profiteering. The 41 members of Company D of the Second Light Artillery were especially vulnerable to Confederate sharpshooters as they tried to position their guns on the earthworks above the assembling Confederate troops preparing for their assault on the fort. However, the guns could not be lowered to a firing angle that was effective against the ditch and ravine below the earthworks. As they labored fruitlessly, they were easily picked off by Confederate sharpshooters.

Most of the white Union soldiers in the fort were the five companies of William F. Bradford’s West Tennessee battalion of the Thirteenth Union Tennessee Cavalry, about 295 men. Most of the 64 Confederate deserters in the fort were among Bradford’s cavalry, but there was a small number of cavalry from other Union regiments, including the notorious Sixth and Seventh Union Tennessee cavalries also reported to have looted, murdered, terrorized, and raped civilians in Kentucky and Tennessee. Like Kirk’s Raiders in East Tennessee and western North Carolina, these Union Tennessee regiments tended to attract Confederate deserters .and opportunistic looters and criminals. Of the 64 Confederate deserters in the fort, only 17 survived.

Some skirmishing had occurred during the morning at a few buildings outside the earthworks. These were taken and occupied by Confederate sharpshooters, exposing the Union artillery men to even deadlier fire. Forrest also positioned 400 sharpshooters under Col. Barteau and Capt. Anderson on both flanks of the 300-yard, two-foot wide path down the shallowest slope of the bluff leading from the back of the fort to the river to prevent union steamships from landing relief troops. Union transports attempted to land later but quickly abandoned the idea under heavy accurate fire.

Forrest, Chalmers, and other staff quickly realized the Union position was weak, and the fort could easily be taken. However, the military gains were only six light guns, a few hundred horses (always badly needed) and several hundred prisoners. However, a frontal attack over the earthworks and breastworks could be very costly.

About 3:30 PM, after Forrest’s ammunition wagons had caught up, under a flag of truce, Captain Walter Goodman, Chalmers’ adjutant, delivered a message to the Union commander, who Forrest still thought was the now deceased Major Booth.

“As your gallant defense of the fort has entitled you to the treatment of brave men, I now demand an unconditional surrender of your force, assuring you at the same time that they will be treated as prisoners of war. I have received a fresh supply of ammunition and can easily take your position. Should my demand be refused, I cannot be responsible for the fate of your command.”

The new Union Commander, Major Bradford of the Union cavalry, could see the Union gunboat New Era approaching on the river and stalled for time, asking for an hour to decide. He also demanded the personal appearance of Forrest, and Forrest came forth. The Union troops nearby had been drinking beer and whiskey for over three hours and began to jeer Forrest and the Confederate contingent with verbal and digital insults. They taunted the Confederate privates present and dared them to attack, saying they would give them “no quarter.” Forrest gave them 20 minutes to decide and repeated verbally to the Union contingent: “If he does not surrender, I will not be responsible for the conduct of my men. Tell him that plainly.” Bradford’s response, possibly thinking this was another of Forrest’s famous bluffs, was: “I will not surrender.” Forrest was visibly angry at the possibility of needless loss of life.

At the signal of a bugler, the Confederate regiments under Col. Bell and Col. McCulloch surged out of the ravine and up to the six to eight-foot earthen parapet. The first row acted as human ladders hoisting up the men behind them. Row after row climbed over the parapet and down into the outer fort. They were covered by enormous barrages of rifle fire by Confederate sharpshooters. This Confederate tactic worked flawlessly with few casualties. Meanwhile the Union gunboat New Era was hit by such intense and accurate fire by Confederate sharpshooters on the bluff that they had to close their gun ports and pull away.

Forrest usually led his men from the front, but may have been too badly injured by the earlier fall from his fatally wounded horse during reconnaissance. Forrest and Chalmers stayed outside the fort until about 20 minutes into the 30 minute battle.

As waves of Confederate soldiers and gunfire poured into the inner fort, confusion reigned supreme, but there was never any surrender. As Confederate attackers surged into the fort, some of the blacks threw down their guns and raised their hands. When the Confederates advanced past them, a few of them retrieved their guns and fired at their backs. Some Confederates decided not to risk being shot in the back and shot anything in a blue uniform regardless of their posture as they advanced. Many were also probably experiencing the insane rage of intense life-threatening close combat.

Confederate Sergeant Achilles Clark, writing to his sisters on April 14, reads in part:

“Our men were so exasperated by the Yankee's threats of no quarter that they gave but little. The slaughter was awful. Words cannot describe the scene. The poor deluded negroes would run up to our men fall on their knees and with uplifted hands scream for mercy but they were ordered to their feet and then shot down. The white men fared but little better. The fort turned out to be a great slaughter pen. Blood, human blood stood about in pools and brains could have been gathered up in any quantity. I with several others tried to stop the butchery and at one time had partially succeeded but Gen. Forrest ordered them shot down like dogs and the carnage continued. Finally our men became sick of blood and the firing ceased.”

The last two sentences, however, are strongly contradicted by other reports, circumstances, and facts. Forrest and Chalmers forcefully, with threat of saber, ordered the firing in the fort to stop, when they saw the battle there was concluded. Chalmers later admitted that several blacks were killed by over-zealous men. Union casualty records for the battle are doubtless incomplete and some suspicious in their accuracy, but the number of men shot while surrendering or disarmed may be as few as ten, and only five of those were black. White Confederate deserters fared much worse than blacks.

Many Union soldiers surrendered at the inner fort, but there was never a formal surrender, and the colors were not cut down by the Confederates until all firing and resistance had ceased. Lieutenant Daniel Van Horn of the Sixth Heavy Artillery (Colored) stated in his official report, "There never was a surrender of the fort, both officers and men declaring they never would surrender or ask for quarter.”

Union Major Bradford abandoned the battle and attempted to escape down the bluff to the river and the protection of the gunboat New Era. Many Union soldiers joined the only path to escape. Judging from the large number of Union rifles since discovered on the bluffs, it must have been a great many men. The Confederates fired after them and received return fire. The narrow 300-yard path, however, was still flanked by 400 Confederate sharpshooters, 200 on each side. It was a terrible gauntlet of fire probably inflicting terrible casualties. The Union gunboat New Era could not open its gun ports because the hail of accurate fire from Confederate sharpshooters and was unable to help them as previously planned. A few may have escaped, but Bradford and probably many others were taken prisoner on the river bank. Bradford later escaped, was captured again, and was either killed trying to escape from four captors or possibly executed.

General Sherman was dubious of the Congressional report as political exaggeration. Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles also doubted the integrity of the politicized Congressional report. Sherman did his own investigation and took no action against Forrest. Sherman thought that there was probably some enmity by some Confederates whose former slaves joined their enemies and that this may have influenced the uneven casualties. However, he believed Forrest’s account of the battle and cited this in his defense: “I was told by hundreds of our men, who were at various times prisoners in Forrest's possession, that he was usually very kind to them.”

From the forming of the USCT units in September 1863, approximately 193,000 blacks served in the Union Army and Navy. Only 2,800 were killed in battle or died of wounds. Close to 50,000 are estimated to have died of disease or other causes.

It is my opinion, formed by researching this article, that the number of black soldiers killed while trying to surrender at Fort Pillow has been greatly exaggerated for political reasons both then and now. Perhaps General Chalmers best described it as “several.” A dozen would seem the upper limit. Black Union soldiers at Fort Pillow died at twice the rate of whites, but Confederate sharpshooters naturally concentrated on destroying the threat of Union artillery. Moreover, the report of Lt. Van Horn of the Sixth Union Artillery Battalion, citing their resolve never to surrender or ask for quarter, certainly indicated a much higher motivation among the black soldiers to fight than among Major Bradford’s Unionist cavalry.