Two Invaluable Alabama Slave Narratives

From 1936 to 1938, during the Great Depression, the Roosevelt Administration through the Work Projects Administration and the Federal Writers Project, sponsored by the Library of Congress, collected about 2,300 interviews of former slaves. The purpose was to preserve the personal memories of what life was like for slaves before and during the Civil War. All of these are now available online and organized by state. The best and easiest source is the Gutenberg Project at Gutenberg.org under the title, Slave Narratives—Project Gutenberg.

I have quoted portions of several of the Mississippi Slave Narratives in my book, The Un-Civil War: Shattering the Historical Myths, in the chapter, “Slavery in Fact and Fiction.” The State volumes of Slave Narratives, along with Fogel and Engerman’s formidable academic study on the economics of Southern slavery published in 1974 as, Time on the Cross, are the two richest and most scholarly resources on what Southern Slavery was really like. Yet because they present a surprisingly benign historical account of Southern Slavery opposed to what is now fashionable, even hysterically obligatory, in academic, media, and political circles, they are unfortunately neglected, suppressed, or verboten.

There are a wide variety of accounts, and some demonstrate embarrassingly harsh discipline and the tragic sorrow of separation of families when slaves were sold. One is first struck by the relief that slavery no longer exists. Yet these narratives also reveal an astonishing prevalence of mutual affection between slaves and masters and many positive reminiscences of the actual conditions of slavery. Many of the more positive than expected living conditions are strongly supported by Fogel and Engerman. One is also struck by the remarkable prevalence and constant reference to Christian beliefs and obligations in both slaves and masters. Most slaves thought well of their masters, who often demonstrated a high sense of moral duty to the welfare of their slaves. The most frequent criticism was of overseers or field “drivers,” many of whom were African-Americans.

The language of the former slaves is colorful. In fact, delightful. Nobody but the most brainwashed political correctness pin head would change a word or spelling. Two complete interviews follow.

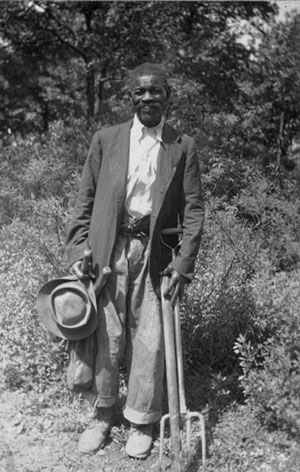

Interview with Gus Brown by Alexander B. Johnson, Birmingham, Alabama

Gus saw Mass’s hat shot off.

"They is all gone, scattered, and old massa and missus have died." That was the sequence of the tragic tale of "Uncle" Gus Brown, the body servant of William Brown, who fought beside him in the War between the States and who knew Stonewall Jackson.

"Uncle Gus" recalled happenings on the old plantation where he was reared. His master was a "king" man, he said, on whose plantation in Richmond, Virginia, Uncle Gus waited on the tables at large feasts and functions of the spacious days before the War. He was entrusted to go with the master's boys down to the old swimming hole and go in "washin." They would take off their clothes, hide them in the bushes on the side of the bank, put a big plank by the side of the old water hole “and go in diving, swimming and have all the fun that youngsters would want,” he said.

Apparently his master's home was a plantation house with large columns and with all the glitter and glamour that the homes around Richmond have to offer. About it were large grain storage places for the master was a grain dealer and men on the plantation produced and ground large quantities into flour.

Gus worked around the house, and he remembers well the corn shuckings as he called them on which occasions the Negroes gave vent to emotion in the form of dancing and music. "On those occasions we all got together and had a regular good time," he said.

"Uncle," he was asked, "do you remember any of the old superstitions on the plantation? Did they have any black cat stories?"

"No sir, boss, we was educated Negroes on our plantation. The old bossman taught his Negroes not to believe in that sort of thing.”

"I well remember when de war came. Old massa had told his folks befo' de war began dat it was comin', so we was ready for it.”

Beforehand the master called all the servants he could trust and told them to get together all of the silver and other things of value. They did that, he explained and afterward they took the big box of treasures and carried it out in the forest and hid it under the trunk of a tree which was marked. None of the Negroes ever told the Yankees where it was so when the war ended the master had his silver back. Of course the war left him without some of the things which he used to have but he never suffered.

"Then de war came and we all went to fight the Yankees. I was a body servant to the master, and once a bullet took off his hat. We all thought he was shot but he wasn't, and I was standin' by his side all the time.”

"I remember Stonewall Jackson. He was a big man with long whiskers, and very brave. We all fought wid him until his death.”

"We wan't beaten, we was starved out! Sometimes we had parched corn to eat and sometimes we didn't have a bite o' nothin', because the Union mens come and tuck all the food for their selves. I can still remember part of my ninety years. I remembers we fought all de way from Virginia and winded up in Manassas Gap.”

"When time came for freedom most of us was glad. We liked the Yankees. They was good to us. 'You is all now free. You can stay on the plantation or you can go.' We all stayed there until old massa died. Den I worked on de Seaboard Airline when it come to Birmingham. I have been here ever since.”

Interview with Hattie Clayton by Preston Klein

“De Yanks Drapped Outen de sky.”

'Aunt' Hattie Clayton said, "I'se gittin' erroun' de ninety notch, honey, an' I reckon de Kingdom ain't fur away."

S She lives in a tiny cabin not far from Opelika. Her shoulders are bent; her hair gray, but she still does a large amount of housework. She likes to sit on the tumbledown front porch on summer afternoons, plying her knitting needles and stretching her aged legs in the warm sunlight.

"'Twas a long time ago, honey," she observed when talk of slavery days was brought up, "but I 'members as ef 'twas yestidy. My ol' mistus was de Widder Day. She owned a plantation clos't to Lafayette an' she was mighty good to us niggers.”

"Ol' Mistus boughten me when I was jus' a little tyke, so I don't 'member 'bout my pappy an' mammy.

"Honey, I 'members dat us little chilluns didn't go to de fiel's twel us was big 'nuff to keep up a row. De oberseer, Marse Joe Harris, made us work, but he was good to us. Ol' Mistus, she wouldn't let us wuk whin it was rainin' an' cold."

Asked about pleasures of the old plantation life, she chuckled and recalled:

"I kin heah de banjers yit. Law me, us had a good time in dem days. Us danced most eb'ry Sattidy night an' us made de rafters shake wid us foots. Lots o' times Ole Missus would come to de dances an' look on. An' whin er brash nigger boy cut a cute bunch uv steps, de menfolks would give 'im a dime or so.

"Honey, us went t' de church on a Sundays. I allus did lak singin' and I loved de ol' songs lak, 'Ol' Ship of Zion,' an' 'Happy Land.' Ol' Mistus useter take all de little scamps dat was too little for church an' read de Book to dem under de big oak tree in de front yahd."

"Aunt Hattie," she was asked, "do you remember anything about the War between the States?"

"You mean de Yankees, honey?"

"Yes, the Yankees."

Her coal black face clouded.

"Dey skeered us nearly to death," she began. "Dey drap right outen de sky. Ol' Mistus keep hearin' dey was comin', but dey didn't nebber show up. Den, all ter once, dey was swarmin' all ober de place wid deir blue coats a-shinin' an' deir horses a'rarin'.

"Us chilluns run en hid in de fence corners en' behin' quilts dat was hangin' on de line. An' honey, dem Yankees rid deir horses rat onto Ol' Mistus flower beds. Dey hunted de silver, too, but us done hid dat.

"I 'members dey was mad. Dey sot de house a-fire an' tuk all de vittals dey could fin'. I run away an' got los', an' whin I come back all de folks was gone."

'Aunt' Hattie said she "wint down de big road an' come to a lady's house where she remained until she married.

"Us moved to Lafayette an' den to Opelika," she concluded, "an' I bin' here eber since."

She lives with one of her numerous granddaughters now. She finds her great happiness in "de promise" and the moments when she can sit in the shade and dip her mind back into memory.

***

Many of the Slave Narratives have photos of the former slaves. Unfortunately, the narrative of Hattie Clayton did not include a photo.

One of the things I have noticed about sincere Christians during the Civil War, “slavery times,” and my lifetime is that they have a spirit of forgiveness. How different that is from the virtue-signaling, hyper-politically-correct, cancel-culture hysteria that prevails in academia, media, and the politics of recent decades. The present spirit of arrogant enmity is perhaps most obvious in Critical Race Theory and other Social Marxist forms of bullying that are weakening and dividing our country even in the face of severe existential threats to American freedom and prosperity.