We all claim to admire people who persevere despite handicaps, hardships, family, health or financial difficulties, etc., until they reach their goal. Let’s define “Perseverance”. According to Webster’s dictionary, it is defined as: “continued effort to do or achieve something despite difficulties, failures, or oppositions.” That definition is pretty straightforward, and most of us can agree with it. However, there is much “blood, sweat, and tears” between the dictionary definition and the actual following through to the end goal of one’s perseverance. The key words of the definition are: ‘continued effort’, often for years, and sometimes under severe stress or in great pain!

Former House Speaker Newt Gingrich has a definition of “perseverance” that is right to the point: “Perseverance is the hard work you do AFTER you get tired of doing the hard work you already did.” Or, as Dr. Bob Jones, Sr. always used to say: “Keep on keeping on” until you accomplish what you’ve set out to do. I’ve previously discussed with you, my faithful Times Examiner readers, how much I love “classical” music. However, this article is not about the music that I love, but about three very special and unique people who devoted their lives to bringing that classical “music of the ages” to everyone who would listen to, learn about, and absorb into their finite human minds the almost “celestial” music that has helped to fashion the ‘better natures of mankind’ for over 400 years .

One of these ‘special and unique’ people was a Titan of classical music composition who died long ago, in 1827. One was a young cellist, potentially the greatest cellist of the 20th century (or to be accurate—ANY CENTURY), whose performance excellence flashed across our musical world for only about 12 years, and then flamed out when her artistry was tragically cut short in 1973. One is a retired classical pianist, currently 94 years old (and a ‘snail mail’ acquaintance of mine) who was, by all accounts and by my awed adulation of him, one of the very greatest classical pianists during the middle of the 20th century, and one of the men who first introduced me, via one of his early recordings, to the glories and soul-shattering beauty of the music he played to perfection. All three of these musical artists suffered from a physical malady that would have “shut down” most people, and surely would have discouraged most not-firmly-committed musical artists from continuing on their quests for musical immortality, thus destroying their dreams before they became well established. But these three persevered for their entire musical careers, as long or as short as they were, and left us such works of beauty, passion, and uniqueness that they must surely be included among the “musical immortals” who reside on the Mt. Olympus of classical music, which exists in the minds and souls of their devoted musical followers, one of which is myself.

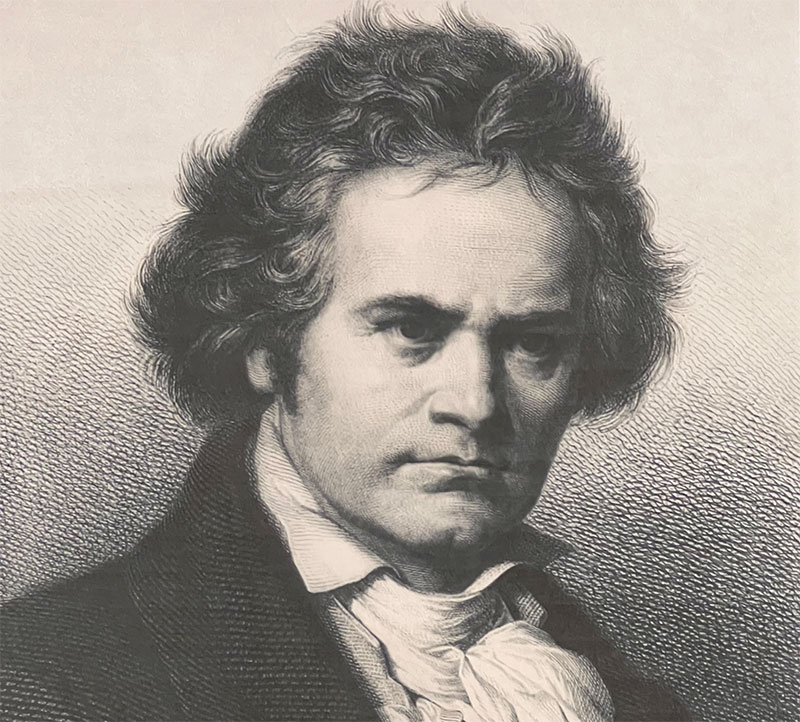

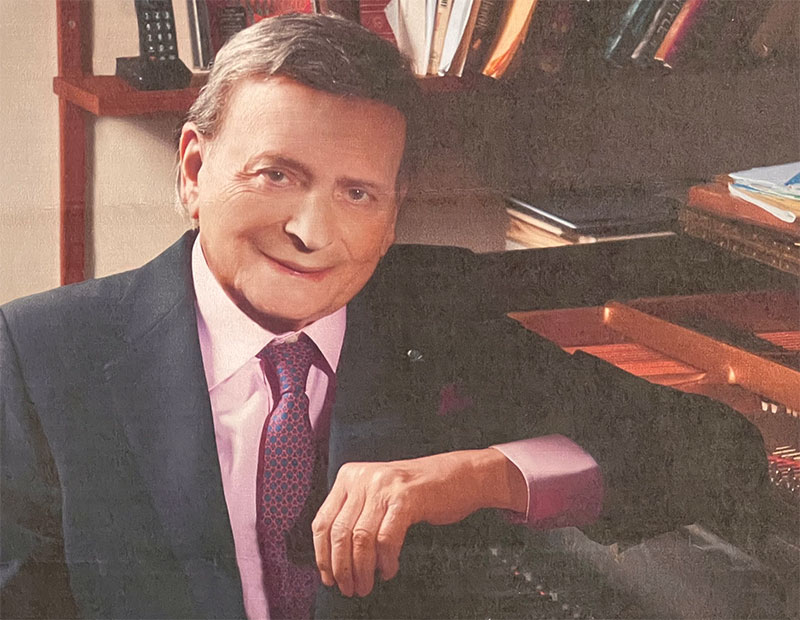

Of these three inspired musical artists I’m going to tell you about, probably only one of them is familiar to the general population of Americans, unless one is, as am I, a long-time aficionado of their music and their accomplishments. The first and probably most familiar artist was LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN (1770-1827), considered by many as the greatest classical music composer of all time, in spite of the fact that he composed many of his greatest works while he was partially or totally DEAF. I believe he was the greatest, even though it pains me to put on slightly “lower pedestals” several other composers whose music I revere and adore. The second musical artist was the great young cellist, JACQUELINE du PRE’ (1945-1987), whose fabulous career was tragically cut short by the terrible disease of multiple sclerosis, which eventually devastated her musical ability after only 12 years of superlative performing, and in 1973 ended what would probably have been a stellar career spanning 50 or 60 years. Sadly, that disease took her life at age 42, after having fought it for 14 years. The third, and final, musical artist is the incomparable ‘maestro’, BYRON JANIS, who performed his first piano concerto with a symphony orchestra (the NBC Symphony Orchestra conducted by the legendary Arturo Toscanini) in 1943 at age 15, a keyboard artist who performed for many years with the terrible and very painful affliction of psoriatic arthritis in both of his hands and wrists, but who performed to the very highest standards in spite of the pain, but whose concert career also was eventually cut short by that debilitating disease.

Non-musicians might ask why a musical artist would continue to compose or struggle to perform despite suffering from serious health issues, including severe pain. One might just as well ask why they would continue to breath. They did their best to continue to make music through the pain, because THEY HAD TO DO SO! All three of these very unique and superbly dedicated musicians “marched to the beat of a different drummer”, and paid whatever price was required in order to leave the world a better and more beautiful place than it would have been had they never lived and excelled in the classical music realm.

Young Ludwig van Beethoven’s family originated in Belgium. His parents were citizens of the Kingdom of Germany. His father, Johann, was a mediocre musician and singer at the Royal Court of Bonn, for which he was paid a meager salary. Unfortunately, Johann was an incurable alcoholic whose life slowly spiraled downward. His mother was described by those who knew her as “a gentle, retiring woman with a warm heart”. Ludwig always referred to his mother as his “best friend”. Some accounts indicate that he was terrified of his father. At a very young age, Ludwig took a serious interest in music and the pianoforte (which is what pianos were called then—although they had only 58 keys instead of the 88 keys that modern pianos have had since the 1850’s), and his father, when he was sober enough, taught his son day and night after he returned from his own musical practice or from the local tavern. Young Ludwig was very musically gifted, and surely his father saw him becoming a new Wolfgang Mozart, who himself had been a child pianoforte prodigy and one of the most famous composers in Europe at the time.

It has always been claimed that Johann Beethoven beat young Ludwig when he failed at accomplishing something during the long practices on

the pianoforte; it has even been claimed that the elder Beethoven often awoke his young son after midnight and forced him to resume practice far into the night (although these contentions have been discounted by some musical historians). By the time that Ludwig was 14, he was appointed organist of the Court of Maximillian Franz, the Elector of Cologne. This enabled him to circulate in new and prominent social circles, and make lifelong friends.

Prince Maximillian Franz became aware of young Ludwig’s early musical compositions and his talent on the pianoforte, and sent him to Vienna in 1787, where it is said he met Mozart. However, he was recalled back to Bonn when his mother died that same year. He returned to Vienna in 1792, and took piano lessons with prominent musicians and composers, and began to astonish that cultural mecca with his virtuosity on the piano. Over the next few years he became a sought-after piano soloist. But by 1801, at the height of his acclaim, he told friends at Bonn that he feared he was slowly going deaf. Depression began to plague him, and he actually considered suicide. During these years he began increasingly to compose brilliant works for the piano, violin, and cello, and for the symphony orchestras of Germany and Austria, at the same time that his increasing deafness slowly put an end to his pianistic solo performing career.

People have always asked: How can a person compose any musical composition, particularly a long sonata or an even longer concerto or symphony, without hearing the music he was composing? But we know that those who are blessed with the ability to compose the greatest of musical compositions DO hear all the notes---IN THEIR MINDS. Ludwig Beethoven composed many of his most brilliant works, from the late 18teens onward, while he was either partially deaf or totally deaf. He “heard” his compositions in his mind, the same as I “play” the music of composers I love in MY mind. Probably his greatest and most famous composition, the immortal Ninth Symphony, the world famous “Ode To Joy”, was completed in 1823 when Ludwig was totally deaf. It was said that Beethoven himself “conducted” the first performance of his Ninth Symphony, hearing the notes he had written in his mind, while another conductor, who was not deaf, stood behind him and did the actual conducting for the singers and the orchestra. What would the world have been deprived of had Ludwig van Beethoven succumbed to depression over his increasing deafness and committed suicide? I don’t even want to contemplate such a disaster. Thankfully he rose above his physical impairment and the personality “quirks” it caused, and left mankind glorious and inspired musical compositions that might be equaled by some composers, but never excelled. He died young at age 56, greatly lamented over much of Europe. But through his music he will “live” forever!

For one brief shining time of musical excellence, from 1961 to 1973, Jacqueline du Pre’ and her 1712 Davidov Stradivarius cello blazed across the classical music world, playing compositions with such brilliance and intensity and feeling that, despite her tragically short career, she is now regarded as one of the greatest cellists of ALL TIME! Only 28 when multiple sclerosis attacked her and eventually forced an end to her performing career, she bravely battled this terrible illness for many years until it killed her at age 42, in 1987.

When she was 4 years old, du Pre’ heard the sound of a cello on the radio and asked her mother for “one of those”. Her mother was her first teacher, who soon enrolled her daughter in the London Violoncello School at age 5. In 1956, at age 11, du Pre’ won the ‘Guilhermina Suggia’ Award, which was renewed for her each year until 1961. This award financed her tuition at the prestigious Guildhall School of Music in London, and for private lessons with a famous cellist. Jacqueline appeared in and won many local music competitions during her teen years, even appearing on BBC Television. At age 16 du Pre’ made her formal debut in London, and at the age of 17 she made her concerto debut at the Royal Festival Hall with the BBC Symphony Orchestra.

For the next ten years du Pre’ performed all of the cello repertoire (concertos and sonatas) with famous orchestras, became friends with well known musicians such as Yehudi Menuhin, Itzhak Perlman, Zubin Mehta, and Pinchas Zukerman. Eugenia Zukerman judged du Pre’ as “one of the most stunningly gifted musicians of our time.” She married the great pianist and conductor, Daniel Barenboim, in 1967 and her life and musical career appeared to be at the pinnacle of success and fame. But in 1971 her playing excellence began to slowly decline as she mysteriously began to lose feeling in her fingers and other parts of her body. Du Pre’ realized that her health was deteriorating, but struggled to carry on her performing schedule before making her last public concerts with the New York Philharmonic, in February of 1973. In October of that year she was finally diagnosed with multiple sclerosis, when her condition became severe. Realizing that she could no longer play her cello with the highest level of excellence as before, she cancelled her final concert and spent her remaining 14 years battling her disease.

I have her recording of the Dvorak Cello Concerto, with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra conducted by her husband, Daniel Barenboim, that she recorded before being afflicted by MS. It is the greatest version of that concerto I’ve ever heard, and stands at the very apex of musical greatness, so much so that it often gives me “goose bumps” when I listen to it. In 1968, Du Pre’ and her conductor husband performed this concerto in a concert to stand in solidarity with the people of Czechoslovakia, who had just been invaded by the military of the Soviet Union. This version is available on UTube (during which she broke her bow strings), and I recommend that classical music fans do themselves a favor and watch and listen to a performance that is unlikely to ever be surpassed. (UTube has more of her performances and her life story.) Her early death was a tragic loss to humanity and to the world of classical music.

Now I come to the man who introduced me, via one of his recordings in 1959, to the world of classical music. Actually I had begun to “explore” that world after I entered university. In 1955 I took a “music appreciation” class conducted by a professor who was a thorough devotee of classical music and who put his love of that genre into my soul. It was through him, and also through the lady who would become my future mother-in-law in 1959, and whose own father had been a concert pianist and piano teacher for many years, that I acquired my love of the music of the ages, a love that has only grown deeper and more introspective over all of the intervening years.

Byron Janis was a musical prodigy, similar to what Mozart had been. His parents recognized his musicality when he was in kindergarten in 1933, and arranged his piano study with a gifted pianist until he was 8. At age 16 he was chosen by the great pianist, Vladimir Horowitz, as his first student. In 1946, at age 18, Byron Janis became the youngest musical artist to ever be signed to a recording contract by RCA Victor Records (which is where I first heard him play). In 1948 Janis made his Carnegie Hall debut at age 20 and was an “unparalleled success”.

Janis was chosen as the first American piano soloist to participate in the 1960 Cultural Exchange between the U.S. and the old Soviet Union, and was called by the New York Times “an ambassador in breaking down ‘cold war’ barriers”. “Booed” and disrespected by Russian audiences at the beginning of his concerts because he was an American, by their conclusions he was given wild applause and, as Janis recalled, the Russians were coming up to the front of the stage and weeping because they had been so moved by his playing. Janis’ musical career was proceeding stunningly. After a failed first marriage, in 1966 he met and married the famous artist, Maria Cooper, the daughter and only child of famed Hollywood actor, Gary Cooper. They’ve been married 56 years.

But the “good times” came with a price. In 1973 Janis began to develop the horrific disease of psoriatic arthritis in BOTH HANDS AND WRISTS, potentially a career ending affliction for a pianist. He struggled on for about 10 years, using medications and drugs to ease his pain and allow him to continue to play. He sought new medications and therapies to ease the increasingly debilitative pain. For all this time, Janis tried to hide his affliction because, as he said, orchestral managers

and conductors usually don’t look kindly upon soloists who have admitted health issues which might cause performance “problems”.

Finally, at a White House recital for Nancy Reagan and her friends in 1985, Janis admitted publically, there in our White House, his battle with the very painful psoriatic arthritis, and told the world that “I have the disease but it doesn’t have me!” About this time, he became the

first Ambassador for the Arthritis Foundation, and still works as his advanced age allows with children and adults who are themselves suffering from severe arthritis. While he had to discontinue his career as a concert piano soloist, and while he went through several painful surgeries on his hands (one of which was botched, and made one of his thumbs SHORTER—a potential disaster for a pianist), Janis has continued to record the music of Chopin and other composers, and has himself composed music for the off-Broadway musical production, “The Hunchback of Notre Dame”, plus much other music, including some of the music for a documentary about his late father-in-law, Gary Cooper, which I watched the first time many years ago.

Back in 2014 I corresponded with Byron Janis, who lives on Park Ave. in New York City. He answered my letter with a nice letter back to me, and told me he was honored that he was my musical “idol”, being one of the first pianists (he was actually the “second” classical pianist I became acquainted with via recordings—the great Artur Rubinstein was my first, and I saw him play LIVE back in 1958) to open my mind to the beauty of the music that he and I, and millions of others, love. Maestro Janis is now 94 years old, and while his concert days are behind him, his legacy of recordings and accomplishments will live as long as there are people on this planet who seek, as Gone With The Wind’s Rhett Butler did, “a culture of grace and beauty” and renounce the anti-culture and the disease of mediocrity that infects so much of American life today.

The great preacher, Charles Spurgeon, commented on this needful human attribute when he said, “By perseverance the snail reached the Ark”. Indeed it did. May our “Persevering Tribe” apply that same trait and may we increase. May the lessons of “perseverance” so well practiced by these three special musical artists inspire all of us to continue to strive for our own excellence no matter the cost, and as Winston Churchill reminded mankind in his own grim “time of testing” back in 1940, “NEVER, NEVER, NEVER QUIT”!