Social unrest, government corruption, economic and financial instability, nuclear weapons, moral depravity — is it too late to save America from destruction? ...

Around the year 720, a man dressed in soldier’s garb knelt within a secret cave deep in the mountains to pray before a forbidden image of the Virgin Mary. The image, which had been hidden in the cave by a local hermit to save it from destruction by Muslim Moorish conquerors, was regarded as the patroness of the region, a remote valley in the Cantabrian Mountains of northern Spain called Covadonga. The man kneeling in prayer was named Pelagius, and he was a Spanish Visigoth and Christian dismayed by what was happening in his homeland. Less than a decade earlier, the Moorish armies of the Ummayad Caliphate had invaded the Iberian Peninsula from North Africa, swiftly conquering most of Christian Spain and Portugal before crossing the Pyrenees into France. It appeared to terrified Christians in Western Europe that, as they had already done in Palestine, Syria, Mesopotamia, and North Africa, the armies of Islam were racing toward a decisive conquest of the heartland of Christianity and the fledgling civilization of the West.

But Pelagius was unwilling to surrender. Deep in the last Christian holdout on the Iberian Peninsula, the remote and forested mountains of Asturias, he prayed for divine assistance and prepared to resist the invader to his final breath. He was the elected leader of the last free state in Spain, and he intended to do his duty.

He had already made his position known by leading a tax revolt against the Moorish authorities, and then expelling the local governor they had installed. Finally, the Moors decided to quash this troublesome rebel and his followers once and for all, and sent a large force, led by two commanders named Alqama and Munuza, to do the job. To the surprise of Pelagius and the Asturians, the Moors were accompanied by a bishop, Oppas of Seville, who had allied himself with the enemy and tried to convince the rebels to surrender.

Pelagius’ band of a few hundred ragtag fighters, greatly outnumbered by the advancing Ummayad forces, withdrew into the narrow, steep-walled valley of Covadonga in the rugged region known today as Picos de Europa, and prepared an ambush. A portion of the invading army, led by Alqama, pursued them. In the narrow space, the Asturians rained arrows and rocks on the Moors from above, before unleashing an attack out of a hidden cave that took the enemy by surprise and led to their rout. Alqama himself was killed in the slaughter, along with many of his men. As the Moors retreated from the valley, ordinary villagers joined in the battle, rallying to Pelagius’ banner and killing most of the fleeing remnants of the army. The other Moorish general, Munuza, not chastened by the setback, soon assembled another force and attempted a second conquest of Asturias, only to be defeated and killed by Pelagius and his new army of Asturian patriots.

As a result of the victory at Covadonga, Asturias was established as an independent Christian state, with Pelagius its founding father. It became the source of a more than 750-year war waged against the Moorish occupiers, known as the Reconquista or Reconquest. Not until 1492, with the fall of the Moorish kingdom of Grenada, was the Reconquista complete. It not only stands as the longest war in human history, but also demonstrates the extraordinary resilience of Western Christian civilization. The spark kindled at Covadonga led to the establishment of two of the greatest Western nations, Spain and Portugal, and to their roles in exploring and colonizing much of the world in the modern age.

Pelagius could not have imagined the far-reaching consequences of his heroism. But his is only one example of how often, across the centuries, the West has overcome seemingly insurmountable odds and risen to new heights.

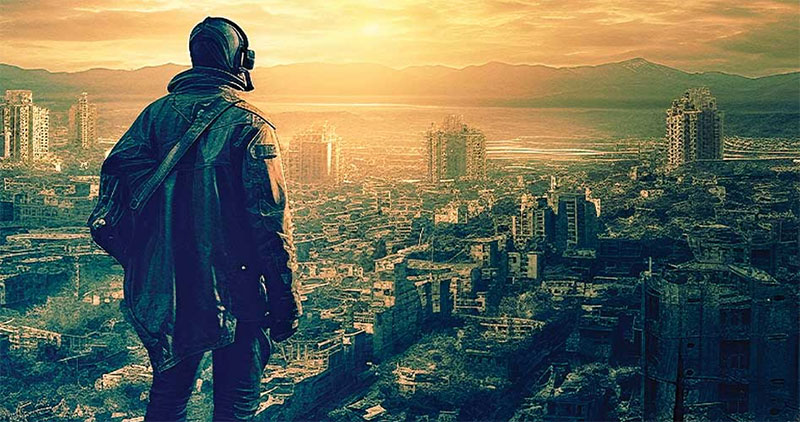

While the Moorish hordes are extinct, it could be plausibly argued that the status of modern-day America is no less precarious than that of Pelagius’ Spain. Our security is threatened, not by Islamic conquerors, but by a duo of nuclear superpowers and a tide of illegal immigrants, including enemy infiltrators, pouring across our southern border at the invitation of our own political leaders. Our body politic is being undone from within, not by a single treasonous cleric, but by a veritable army of subversives, not only in the government, but in the media and every important cultural institution. We literally live in a time when our morals have become so degraded that it is fashionable to call good evil and evil good, and when enemies from without and within, better armed and more bitterly determined than ever before, seem poised to dismember our fair Republic and to uproot and destroy the very foundations of Western civilization.

This is why so many now despair of ever saving our civilization and our freedoms. Too many have decided that the end is at hand, and that the only thing remaining is to prepare for the inevitable collapse. America is a lost cause, they believe, and there is no prospect of restoring her former greatness.

In such matters, history is no sure guide. Spengler, Barzun, and many other historians have considered the decadence of the modern age as akin to the decline of Rome or Byzantium, the symptom of the internal rot that precedes collapse as surely as twilight precedes night. And while the decline and fall of so many antecedent civilizations do suggest parallels with our perilous times, history is also replete with instances of hopeless causes that persevered and even flourished against all odds.

Overcoming Hopeless Odds

Western civilization itself is such a cause. The hybrid offspring of Greco-Roman classical civilization and Judeo-Christianity, Western civilization was very nearly extinguished in the cradle by its own nursing mother, the Roman Empire. A product of the Jewish culture in Roman Judea, the upstart Christian religion spread rapidly across Roman dominions, despite concerted efforts by Roman authorities, from Nero onwards, to stamp out Christianity by any means necessary. Once Constantine the Great was converted and declared Christianity the official religion of the Roman Empire after three centuries of persecution, it might have seemed that the final victory for the new faith had been achieved. In both the Eastern and Western Empires, Christian churches proliferated, and the religion was both spreading beyond the imperial boundaries and taking root among new immigrants, such as the Germanic Goths, who were moving into imperial territory.

But in the mid-5th century, the Western Roman Empire, including the Eternal City of Rome itself, collapsed, leaving the Eastern Empire, with its glittering capital Constantinople, as the sole repository of wealth and power in Christendom. And the Eastern Roman Empire, now known as the Byzantine Empire, lived dangerously for its entire 1,100-year history. During that time, it was assailed by wave after wave of hostile invaders, including formidable barbarians such as the Avars, Petchenegs, and Bulgars, as well as the almost-unstoppable armies of various Islamic powers, including the fanatical onset of the soldiers of the Rashidun Caliphate, and both the Seljuk and Ottoman Turks. On several occasions, the Byzantine emperor himself was killed or captured in battle, as when Nikephoros I was captured and put to death by the Bulgarian Khan Krum and his skull fashioned into a drinking goblet by that same barbaric potentate, or when Romanos IV was captured by the Seljuk Turkish Sultan Alp Arslan at the disastrous Battle of Manzikert and forced to kneel while his captor placed his foot on his neck. Byzantium even suffered at the hands of fellow Christians, most notably when Constantinople was sacked by the Venetian-led forces of the Fourth Crusade, who were diverted from their objective in the Holy Land by the riches of the Byzantine capital.

During these and many other times when enemy forces were massed outside the gates of the medieval bulwark of Christendom, the cause must have seemed hopeless. And when Constantinople finally fell to the Ottomans in 1453, due in no small measure to the refusal of Western European powers to come to its aid, the shock and fear felt across the West was tremendous. And, as it turned out, those fears were justified. Without Byzantium to blunt the Islamic foe, Ottoman forces poured unimpeded into Europe and island-hopped across the Mediterranean. It then fell to the often-divided and enfeebled forces of the West to defend the heartland of Christian civilization against the Turkish invaders as best they could, often fighting a valiant but losing campaign, as with the heroic resistance at Rhodes that was finally quashed by Suleiman’s forces. Until the naval battle at Lepanto in 1571 that resulted in the first major victory of a Western alliance against the Ottomans, few believed that the relentless advance of the Turks could be stopped. Too often, Western Christian powers were their own worst enemies, consumed with fighting one another instead of uniting against a common foe. England and France, for example, spent more than a century locked in a ruinous war over dynastic succession that lasted from the late Middle Ages into the Early Modern Period. And no sooner was the Hundred Years’ War ended (the same fateful year that Constantinople fell) than England descended into a horrendous civil war, the Wars of the Roses, that dragged on for three more decades.

With the rise of Protestantism came decades of desolating religious wars in Western Europe, culminating in the horrors of the Thirty Years’ War in the first half of the 17th century. England, spared the brunt of that continental effusion of bloodletting, spiraled into another civil war that saw a king beheaded and the monarchy temporarily replaced by an unstable commonwealth. On the other side of the North Sea, the other great bastion of progress and liberty, the Dutch Republic, was tied down in the Eighty Years’ War against the Spanish, in a long and bloody bid to win independence.

Nor were wars the greatest threat facing the still-adolescent West in the Early Modern Period. The Black Death pandemic, which had wiped out one third to one half of the entire population of Europe in the mid-14th century, effectively destroying the civilization of the High Middle Ages and clearing the slate in Italy for what became the Renaissance, had never really gone away. At intervals of approximately 10 years, the plague re-emerged and wreaked havoc again and again throughout the 14th through the 17th centuries. While it never again achieved the apocalyptic contours of the initial onset, it continued to selectively desolate regions of Western Europe, including many devastating repeat performances on the Italian peninsula, until the late 1600s.

A time to die: The Black Death pandemic of the 14th century, which killed between one third and one half of the entire human population, remains the greatest disaster in human history. But instead of destroying Western civilization, the plague ultimately created the conditions for it to rise to greater heights.

Yet somehow Western civilization turned all these epochal setbacks into strengths. The religious wars, devastating though they were, led to greater tolerance and to the Westphalian framework with its concept of the nation-state that honored the sovereignty and right of self-determination of countries large and small. The bubonic plague not only destroyed medieval feudalism, clearing the way for the implementation of modern notions of limited government and equality under the law, it also proved a tremendous stimulus for cultural and scientific advance. It is no accident that Florence, the city-state that gave birth to the Renaissance, also suffered an 80-percent mortality rate during the Black Death, one of the greatest of any population center. Among the Florentine survivors of the pandemic was Giovanni Bocaccio, an eminent writer whose greatest work, the Decameron, set in the time of the Black Death, was published a few years after the Black Death ended in Italy. One of his closest friends was fellow Florentine (but then-resident of Padua) Francesco Petrarch. These two men, whose lives spanned two ages, were largely responsible for initiating the Renaissance, a movement whose next generation saw the rise of Da Vinci, Michelangelo, and Pico della Mirandola.

In a later century, a young and undistinguished university student, Isaac Newton, was relieved for two years of his academic duties at Cambridge University because of another major plague outbreak, the Great Plague of London, in 1665-1666. During those two pivotal years, Newton remained in his native village of Woolsthorpe-by-Colsterworth and used his time to invent calculus and to develop his theories of optics and gravitation, ushering in the greatest scientific revolution in history.

These and many more such examples show a pattern in the history of the West. More often than not, faced by seemingly insurmountable odds — desolating pandemics, horrifying internecine wars, bids for conquest by formidable foreign enemies — Western civilization has managed to turn challenges to strengths. Not only that, but by the end of the 17th century, the West embarked upon an unprecedented three-century rise to a pinnacle unexampled in human history. During that time, the march of the West — cultural, political, scientific, and technological — seemed unstoppable. Western culture, religion, and learning spread across the world, far eclipsing the static, oligarchic cultures of Asia and Africa. During that period, though challenges persisted — a French Revolution here, a World War or Cold War there — nothing seemed insuperable. The story of the 19th and 20th centuries in particular was of worldwide Westernization that brought in its train individual liberty, modern medicine and travel, computers, air travel, the internet, and other fruits of a seemingly bottomless cornucopia of progress.

Perilous Times

But now, the West, rather than facing unprecedented peril, merely finds itself back in the more precarious posture of centuries past, a posture we have forgotten in the flush of recent success. The combined militaries of Russia, China, and North Korea are formidable indeed; but are they any more so in our time than the Moors, Mongols, and Ottomans were in theirs? The Covid pandemic and its political and social effects have indeed been traumatic — but far less than was the Black Death and its three-century aftermath, a period that saw some princes forcibly wall entire families inside their own homes, to perish together, if any member of a household caught the plague. The recent disintegration of morals and exaltation of every species of perversion is a dismaying spectacle indeed, but past centuries have seen their fair share of abominations, from depraved Medieval serial-killing nobility, such as France’s Gilles de Rais and Hungary’s Elizabeth Bathory, to celebrated satanists and their coteries of admirers, such as 18th-century England’s Francis Dashwood and his Hellfire Club or revolutionary France’s Marquis de Sade. Indeed, the 19th century, perhaps the pinnacle of peace and power for the West (the American Civil War being a notable exception), gave birth to revolutionary communism and many of its radical socialist sibling ideologies, some of which advocated sexual debauchery and atheism amid the devout Christian culture of early America.

Formidable foes: The doomsday weapons now wielded by enemy powers are far more lethal than the mightiest militaries of ages past. But they are better suited as instruments of intimidation than of conquest. (AP Images)

In a word, every time is a time of crisis, and every generation fancies itself uniquely challenged.

None of which is to minimize the very real and acute problems now faced by America and the wider Judeo-Christian West, a region that encompasses, or until recently encompassed, the United States, the United Kingdom, Australia, Canada, New Zealand, most of Latin America, and large parts of Europe, with several Asian and African nations, such as Israel, South Africa, the Philippines, and even South Korea, Japan, Taiwan, and Singapore, having hybridized substantial portions of Western culture with their own. If we include countries such as Russia and India as being partly Westernized, a fair argument could be made that half of the world’s population identifies at least in part with Western values, while nearly all of the rest partake of some of its cultural and technological fruits. This being the case, how can the West, and especially its leading light, the United States, have reached such a critical pass?

To a large degree, we seem to be victims of our own success. As long as our culture was beset by deadly foes, we rose to the occasion, as happened in Spain during the Reconquista. There have been many such examples of farsighted, persistent valor in Western history. But today, benumbed as we have become by our artificial world of sound bites and instant gratification, few of us have the attention span or willingness even to read a challenging book, let alone undertake a crusade of centuries.

Why, then, given the historical evidence that Western civilization, including America, is far more successful and resilient than Rome and other bygone civilizations, have so many concluded that it is too late, that our civilization is in terminal decline, and that there is no point fighting to preserve it? Many such defeatists are being deceived by a sophisticated disinformation campaign orchestrated by those who would destroy our civilization. The news media focus on the lurid and bizarre to create the impression that debauchery and outré sexual “orientations” have become the norm, when in fact the vast majority of Americans continue to live heterosexual, family-centered lifestyles. While there has been a decline in religiosity, including both church attendance and belief in God, religion still plays a very prominent role in American society, as her ubiquitous houses of worship attest to even the casual visitor. America has had swings in religious feeling in the past; hence the pattern of revivals and awakenings that has occurred at fairly regular intervals throughout our history. And this pattern of fluctuating religious devotion has also been the rule across the entire sweep of Western history.

But what about political decline, which we document regularly in this publication? Don’t we see a general and irreversible movement in America away from limited government under the Constitution, and into a dictatorial New World Order? Until fairly recently, many trend lines seemed to suggest that.

But since the beginning of this new century, we have seen some dramatic countervailing trends as well, all of which testify that, after all, America and Western civilization are, yet again, veering away from the brink toward a greater future.

Modern marvels: High tech, made possible by Western civilization, has also created a false sense of invulnerability and security that our ancestors did not have. (skynesher/E+/Getty Images Plus)

It Can Be Done

Consider that, in the United States, what once looked like an irresistible movement to nullify the Second Amendment and disarm the American people (e.g., the landmark gun-control bill of 1986 or the 10-year ban on “assault weapons” in 1994-2004) has given way to a wildly successful state-by-state movement toward “constitutional carry” and the popularization of firearms ownership to levels not seen since the Old West. Or consider the recent overturn, unhoped for by many, of Roe v. Wade after a 50-year struggle. Or consider the remarkable new ability conferred by the internet to educate, expose government deception, and propagate truth. Or consider the new campaign against the Deep State and its corrupt operators, as betokened by the election of Donald Trump, as well as the vigorous investigation of Biden family corruption by a House GOP displaying far more backbone and resolve than in the past. Or consider the growing popular pushback against the “woke” counterculture, evidenced by public backlash against the in-your-face ad campaigns of Bud Light and Target, or the defiant popularization of entertainers such as singer Jason Aldean and his anthem of resistance, “Try That in a Small Town.”

And these trend lines do not disappear at the water’s edge. Across the pond, in the birthplace of Western civilization, we see a tremendous backlash across Western and Central Europe, with ordinary Europeans revolting against the secularist, internationalist, and socialist order being imposed on them via the European Union. The last few years have seen a wave of triumphant right-wing, populist, Christian-inspired nationalist movements seize control of governments, from Poland and Hungary in the east to the Netherlands and the U.K. in the west, and from Italy in the south to Sweden and Finland in the north. Of these, the most consequential so far have been the Nigel Farage-led Brexit movement and that of Italy’s dynamic new prime minister, Giorgia Meloni, who is proving the boldest and most articulate defender of traditional Western values that Europe has seen in decades. That Europe, which has suffered so much more than America and has strayed much farther from its civilizational roots in the process, is now effecting such a dramatic turnaround is conclusive evidence, if more be needed, that this conflict is far from over, its outcome far from determined, and the complacent acquiescence of the masses far from a foregone conclusion.

The only question that remains to be answered for Americans is: How much farther will we follow our self-destructive course before the inevitable turnaround, reawakening, and renewal take place? Will we have to experience national bankruptcy, civil war, and perhaps a rain of ruinous modern weapons on American cities before we finally change course? Will we see our cities hollowed out by violence and racial division, and our economy and technology crippled by self-imposed socialist and radical environmentalist policies before we finally arise from the dust and once again unashamedly take advantage of the great natural and civic advantages our nation has always enjoyed? Will we have to experience military defeat at the hands of some foreign superpower, or see some of our territory seized by hostile invaders or waves of illegal immigrants before we see a rebirth of the martial resolve that once enabled us to win and vindicate our independence by defeating the world’s greatest superpower of the day? These and other unanswered questions cloud the future of our Republic. But they should not call into question the long-term viability of our resilient civilization.

In every crisis past, both in America and across the wider West, people have always found ways to rise to the occasion and overcome seemingly insurmountable odds, and this crisis will prove no different. As in times past, the renewal will be preceded by a revival of faith and civilizational values, which in turn will yield to an unshakable resolve to not fritter away the fruits of our forefathers’ sacrifice. As at Covadonga and so many other civilizational turning points, the people will follow principled and visionary leadership and join the contest, however unequal it might appear.

In America, the problem is perhaps more vexing than elsewhere in the West, because America — unlike the nations of Europe with their governments that have traditionally hybridized monarchy and aristocracy with republicanism and the free market with collectivism — has almost completely turned away from the free market and from the pure republican principles of its founding documents. The agency of this radical transformation, the set of interlocking interests hostile to individual liberty embodied by the Deep State and the radical Left, has lately resorted to ever-more bizarre assaults on tradition and religion in order to secure its hold on our political and cultural institutions.

These cunning adversaries are well financed, deeply entrenched, and well protected by a network of laws and institutions designed to perpetuate their privilege. These enemies of freedom and virtue enjoy a carefully cultivated aura of invincibility that, more than any other single factor, has convinced many decent people to give up the struggle. Some choose to go off-grid and prepare for the end, while others take refuge in elaborate legal theories that they claim nullify all government authority. Still others — a distressingly large number, it needs to be said — point to the rot and corruption as an excuse for apathy and inaction. And finally, many take solace in mass entertainment and vice, concluding that transient pleasures and stimuli are more worthwhile than refinement, education, and principled action.

All those who allow themselves to be neutralized along any of these lines fail to understand the first principle of liberty, which is self-government. And self-government of the kind necessary to sustain a complex republic — let alone a civilization — is predicated on moral virtue and on education. For moral virtue, we look, as always, to families, churches, and communities. For education, we have learned to our sorrow that the institutions we once relied upon — our schools, colleges, and universities — have been disfigured almost beyond recognition and converted into potent tools for indoctrination by the radical Left. And our once-free press has been diverted from its original purposes to serve as a propaganda tool for those same radicals. As a result, the task of education falls to families and individuals. This magazine and its parent organization, The John Birch Society, were created both as educational tools and as organizational frameworks for re-enshrining our liberty and routing its enemies. Regardless of the turns on the path ahead, education remains our primary strategy, and our institutional motto bears the stamp of American and Western civilization: Less government, more responsibility, and — with God’s help — a better world.

-------------------------

Source: https://thenewamerican.com/print/is-it-too-late-for-america/