Forty-year Background of Sectional Tariff Conflicts

Part 3 of 8 of a Series on the Morrill Tariff

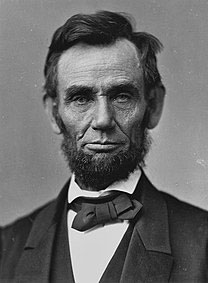

Abraham Lincoln strongly endorsed the newly passed Morrill Tariff during his inaugural speech, and though most of his speech was conciliatory on slavery, he promised to enforce collection of the tariff whether or not the Southern States remained in the Union. After promising that his objective was only to defend and maintain the Union, he added:

“In doing this there needs to be no bloodshed or violence, and there shall be none unless it is forced upon the national authority. The power confided to me will be used to hold, occupy, and possess the property and places belonging to the Government and to collect the duties and imposts; but beyond what may be necessary for these objects, there will be no invasion, no use of force against or among the people anywhere…” (Italic emphasis added.).20

In other words, there would be no Federal violence against Southern states except to collect the tariff and to secure control of the places where it might be collected, for example, Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor. It is obvious from his inaugural speech that Lincoln’s conciliatory words on slavery contrasted with his hard line on tariffs. Raising the tariff was by far his most important objective.

Lincoln met secretly on April 4, 1861, with Colonel John Baldwin, a delegate to the Virginia Secession Convention. Baldwin, like a majority of that convention, would have preferred to keep Virginia in the Union. But Baldwin learned at that meeting that Lincoln was already committed to taking some military action at Fort Sumter in South Carolina. He desperately tried to persuade Lincoln that military action against South Carolina would mean war and also result in Virginia’s secession. Baldwin tried to persuade Lincoln that if the Gulf States were allowed to secede peacefully, historical and economic ties would eventually persuade them to reunite with the North. Lincoln’s emphatic response was:

“And open Charleston, etc. as ports of entry with their ten percent tariff? What then, would become of my tariff?”21a

Despite Colonel Baldwin’s advice, on April 12, 1861, Lincoln manipulated the South into firing on the tariff collection facility of Fort Sumter in volatile South Carolina. (For a thorough account of this, see John S. Tilley’s 1941 book, Lincoln Takes Command.)21b This achieved an important Lincoln objective. Northern opinion was now enflamed against the South for “firing on the flag.” Three days later Lincoln called for 75,000 volunteers to put down the Southern “rebellion.” This caused the Border States to secede along with the Gulf States. Lincoln undoubtedly calculated that the mere threat of force backed by a now more unified Northern public opinion would quickly put down secession. His gambit, however, failed spectacularly and erupted into a terrible and costly war.

Shortly after Lincoln’s call to put down the “rebellion,” a prominent Northern politician wrote to Colonel Baldwin to enquire what Union men in Virginia would do now. His response was:

“There are now no Union men in Virginia. But those who were Union men will stand to their arms and make a fight which shall go down in history as an illustration of what a brave people can do in defense of their liberties, after having exhausted every means of pacification.”22

To appreciate the intensity and bitterness over the Morrill Tariff it is necessary to revisit the history of tariffs in the United States.

The Tariff of 1789, signed by George Washington on July 4, 1789, was primarily a revenue tariff that provided some protection for emerging manufacturing industries. Tariffs supported 100 percent of Federal expenditures in 1792. Between 1789 and 1815 tariffs were raised or lowered as funding needs changed, but the average of all tariff rates, including duty free (zero tariff), ranged from 6.5 to 15.1 percent.23

The War of 1812 began with an American Declaration of War on Great Britain on June 18, 1812, and officially lasted until the Treaty of Ghent on December 24, 1814. But due to communications delays, it extended to January 8, 1815, when American forces under Major General Andrew Jackson defeated British forces attempting to seize New Orleans. Trade tensions were a major cause of the war. Britain was at war with France and in 1807 began to tighten its illegal trade restrictions on the United States in order to prevent any economic benefit to France. The British also feared that the growth of American trade with Europe threatened their Atlantic trade dominance. The U.S. reacted through a series of Congressional bills the same year by banning British imports (the Embargo Act) and then American exports to Britain. Because these acts against Britain were an economic disaster to the American economy—50 percent of American exports and 80 percent of cotton exports went to Britain—they were largely voided by the end of 1809. Tensions, however, continued with the British Navy impressing over 10,000 naturalized American sailors of British origin and confiscating many American ships and cargos. Unable to bear these insults any longer, the American Congress voted a declaration of war against Britain, passing 79 to 49 in the House and 19 to 13 in the Senate. The British responded with a blockade.24

Not a single member of the Federalist Party (formed by supporters of Alexander Hamilton in1794) voted for war. The Federalists, concentrated in New England and the larger cities, favored a more cooperative relationship with Britain and had the most to lose from an interruption in British trade. In fact, the New England states threatened secession in 1807 because of a loss of trade caused by the Embargo Act and other U.S. legislation restricting trade with Britain. In 1814, at the Hartford Convention, they again threatened secession because of the war with Britain. However, the Federalists still retained their belief in Hamilton’s protectionist import policies. This was inherited by the Whigs following the demise of Federalist political power in 1816 and finally by the new nationalist Republican Party in 1856. Ironically, the New England states threatened secession four times, the other two being in 1803 because the Louisiana Purchase threatened their national political dominance and in 1845 because the annexation of Texas diluted their national dominance.25

The British blockade of American ports from 1812 to1815 forced Americans to do their own manufacturing. This began with home manufacturing and became profitable. Most were in New England, New York, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania. The Southern economy remained agriculturally based. By the end of the war, 20 percent of the Northern workforce was engaged in manufacturing, compared to only 8 percent in the South.26

This was the beginning of two sectional interests: one manufacturing and the other agriculture. At the end of the war, the resumption of a flood of lower-priced British manufactured inventory threatened the continued existence of the North’s budding manufacturing economy.

The Tariff of 1816 (or Davis Tariff, named for Treasury Secretary Alexander J. Davis) sought to pay for the war of 1812 and protect America’s emerging manufacturing industry from European, especially British, competition. A tariff of 25 percent was placed on manufactured cotton and woolen imports, with a maximum rate of 30 percent on some goods. Overall, the percentage of Federal revenues from tariffs increased from 46 to 84 percent, and the average tariff on all imports increased from about 6.5 percent to 20 percent by 1820. This was strongly opposed by many in the South who realized that they would incur higher production and living costs and risk disastrous tariff retaliation on raw cotton by the British. It was also unpopular in Massachusetts because they feared the same loss of trade with Britain that they experienced during the war years.27

Thus the stage was set for 40 years of politically intense North-South tariff wars culminating in the Morrill Tariff and Lincoln’s intention to enforce it.

---------------------------------------

Abbreviated Footnotes (FN) 20-27

FN20 - Abraham Lincoln: First Inaugural Address, U. S. Inaugural Addresses.

FN21a - Robert L. Dabney, Discussions Volume IV, Secular, “Memoir of a Narrative Received of Colonel John Baldwin” and “The True Purposes of the Civil War.” (Mexico, Mo.: S. B. Ervin, 1897) Republished by Sprinkle Publications, Harrisonburg, Va., 1994, pp. 94, 104.

FN21b - John S. Tilley, Lincoln Takes Command: How Lincoln Got the War He Wanted, 1941, Nippert Publishing 1991.

FN22 - Dabney, p. 87

FN23 - Tariffs In United States History, U.S. Historical Collections by Federal Government.

FN24 - War of 1812, Wikipedia

FN25 - John S. Tilley, The Coming of the Glory (Springfield, Tennessee, Nippert Publishing, 1949,1995) pp. 67-88.

FN26 - Dallas Tariff (of 1816), Wikipedia

FN27 - Ibid.

Mike Scruggs is the author of two books: The Un-Civil War: Shattering the Historical Myths; and Lessons from the Vietnam War: Truths the Media Never Told You, and over 600 articles on military history, national security, intelligent design, genealogical genetics, immigration, current political affairs, Islam, and the Middle East.

Mike Scruggs is the author of two books: The Un-Civil War: Shattering the Historical Myths; and Lessons from the Vietnam War: Truths the Media Never Told You, and over 600 articles on military history, national security, intelligent design, genealogical genetics, immigration, current political affairs, Islam, and the Middle East.