Above - Captain Eddie Rickenbacker (1890-1973) beside his "Spad" fighter, Fall of 1918. The fuselage insignia was the famous "Hat in the Ring" of the 94th AERO Squadron of which he was the leader. He became America's "Ace of Aces" with 26 German aircraft shot down, for which he was awarded 10 "Distinguished Service Crosses" and "The Medal of Honor."

(I’m indebted to the following two sources for the basics of this story of great courage and determination to survive, a story mostly unknown to Americans of today—but well known to me because Rickenbacker was one of the “heroes” of my youth, and from both of which I quote freely):

- An article titled: “World War 1: American Ace Eddie Rickenbacker”, from THOUGHTCO.COM, by Kennedy Hickman, March 19, 2018;

- An article titled: “Eddie Rickenbacker Adrift in the Pacific Ocean”, from DEFENSE MEDIA NETWORK.COM, by Dwight Jon Zimmerman, November 15, 2012.

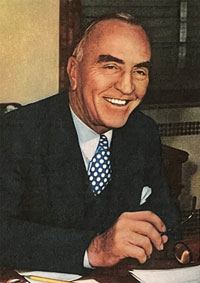

Looking at the historic 1918 photo of Captain Eddie Rickenbacker above the text to this article, one can almost sense the spirit of American accomplishment, the spirit of camaraderie, the determination to ‘let’s get this job done’. Behind the smile was surely an appreciation that he had overcome fear and had survived a year or longer doing battle with a fierce and determined German enemy, which during his early service sometimes included the famous “Flying Circus” led by the “Red Baron—Manfred Von Richthofen”, the 26-year-old “Ace of Aces” of World War 1, who was credited with 80 confirmed shoot downs of Allied aircraft, and who himself was killed during aerial combat in April of 1918.

Edward Vernon Reichenbacher (he ‘Anglicized his name to “Rickenbacker” in 1917 to avoid the increasingly bitter “anti-German” feelings of that time) didn’t start out early in life with intentions to become a flyer. In fact, for much of his early life he was an automobile racer, being obsessed with the rapidly increasing technology and speed being developed by the infant auto industry in the U.S. Eddie was born in 1890, the son of German-speaking Swiss immigrants who had settled in Columbus, Ohio. However, his father died when he was only 12, and Eddie quit school then, ending his formal education to help support his family. As Kennedy Hickman revealed, “Lying about his age, Rickenbacker soon found employment in the glass industry before moving on to a position with the Buckeye Steel Casting Co. Subsequent jobs saw him work for a brewery, bowling alley, and cemetery monument firm. Always mechanically inclined, Rickenbacker later obtained an apprenticeship in the Pennsylvania Railroad’s machine shops. Increasingly obsessed with speed and technology, he began developing a deep interest in automobiles. This led him to leave the railroad and gain employment with the Frayer Miller Aircooled Car Company. As his skills developed, Rickenbacker began racing his employer’s cars in 1910.”

YOUTHFUL RACE CAR DRIVING

During the years from 1910 to 1917 Rickenbacker became quite a success as a race car driver, and even earned the nickname, “Fast Eddie”. He drove a race car in the very first Indianapolis 500 race in 1911, relieving another driver, and drove in that increasingly famous race in 1912, 1914, 1915, and 1916. While he never finished better than 10th place during his racing career at Indianapolis, (in the year 1914), he did manage to set a race track speed record of 134 mph, driving a Blitzen Benz. It was during these racing years that he worked with many pioneers of the automotive industry, including Fred and August Duesenburg. In addition to his growing fame, he managed to earn what was then a very high income, pulling down over $40,000 per year as a race car driver, a huge amount during those early years of the 20th century.

THE PATRIOT JOINS THE U.S. ARMY AIR SERVICE

But it was also during these racing years that his interest in aviation “took off”, so to speak, because of his encounters over those years with men who were pilots in the even more infant aviation industry. Eddie was a devoted patriot, and when the U.S. entered World War 1 in April, 1917 he joined the U.S. Army, hoping to pursue his growing interest in aviation along side of the Army’s growing use of aircraft to combat the, at that time, superior German air power. Rickenbacker immediately offered to form a new fighter squadron of race car drivers, but his superiors refused his offer. Instead, he was selected to be the personal driver for General John J. Pershing, who was the Commander of the American Expeditionary Force in Europe. Increasingly interested in flying, he was nevertheless hampered because he had no college education, and his superiors had judged Eddie as “lacking the academic ability to succeed in flight training.” However, because of his experience repairing race cars in the years before the war, he got a real break when he was assigned to repair the vehicle of the then Chief of the U.S. Army Air Services, Colonel Billy Mitchell, himself destined for fame in future years (and a Court Martial by the U.S. government in 1925 for daring to suggest that air power would soon eclipse the military might of the surface fleet).

Eddie and Billy Mitchell became friends, but at age 27 Eddie was considered to be too “old” for flight training. Soon, however, Colonel Mitchell had pulled enough “strings” and arranged for Rickenbacker to be sent to flight training school. Upon completion, Eddie was commissioned as a First Lieutenant on October 11, 1917. But he was assigned to the base in Issoudun, in France, as an engineering officer because of his former mechanical skills with race cars. He was promoted to Captain on October 28, 1917, whereupon Colonel Mitchell had Eddie appointed as the chief engineering officer for the American base, with permission to fly the fighter planes during his off duty time, but not to fly combat missions.

Despite the initial reluctance of his superiors to allow him to fly combat missions, Eddie did arrange to attend aerial gunnery training in January, 1918 and even completed advanced flight training a month later. He found a suitable replacement for his job as engineering officer for his air base, and applied immediately for permission to join the newest U.S. fighter unit, the soon-to-be-famous 94th Aero Squadron. His request was granted and Eddie arrived at the war front in April, 1918, one of the newest members of the “Hat In The Ring Squadron”, which was destined to become perhaps the most famous American unit of World War 1. Rickenbacker flew his first combat mission on April 6, 1918, and would go on before the war’s end to log over 300 combat hours in the air. He became an “ace” on May 30, 1918 after shooting down two German aircraft in one day.

By September 24, 1918 Eddie had been promoted to command the famous “Hat In The Ring” squadron with the rank of Captain. On October 30, 1918 he shot down his 26th and final enemy aircraft, making him the TOP American pilot of WW1. Returning soon to the U.S., Rickenbacker became the most famous—the most celebrated—aviator in America. He received numerous medals for his achievements, which included the Distinguished Service Cross (8 times), the French Croix de Guerre AND the French Legion of Honor. On November 30, 1930, long after the war’s end, one of his Distinguished Service Cross medals, earned for attacking seven German aircraft (shooting down two) on September 25, 1918, was elevated to The MEDAL OF HONOR by President Herbert Hoover.

POST WORLD WAR 1 YEARS

In 1922 Eddie married Adelaide Frost, and eventually the couple adopted two children. He and several partners started “Rickenbacker Motors”, and that short-lived company became known for bringing racing car technology to the civilian auto industry, including the development of four wheel brakes. Unfortunately his company was driven out of business by the newer and larger auto manufacturers. In 1927 Eddie purchased the Indianapolis Motor Speedway which had helped to make him famous as a race car driver, and he was the one who introduced those famous “banked curves” to that storied track. He operated the Speedway until World War 11 began, and sold it after the end of that conflict. But in 1938, banking on the increasing interest in and success of commercial airline companies, Eddie bought Eastern Air Lines, establishing air mail routes and developing new ways of operating a commercial air carrier. During his tenure with Eastern, the company grew from a small local carrier to one that was nationally known. However, on February 26, 1941, Rickenbacker was nearly killed when the Eastern DC-3 he was a passenger on (on one of which I flew back in 1964) crashed outside of Atlanta. Eddie suffered major injuries, spending months in the hospital, but eventually made a full recovery.

THE ORDEAL OF EDDIE RICKENBACKER

It’s sad that so few Americans today know anything about Eddie Rickenbacker and his service to our nation, and his courage in overcoming extreme challenges. At the beginning of World War 11 he was running Eastern Airlines, but left that company to volunteer his services to the government to “do his bit”. Secretary of War, Henry Stimson, asked Rickenbacker to visit various Allied and U.S. bases in Europe to give an assessment of their operation. Upon completing that assignment, impressing Secretary Stimson with his findings and recommendations, in the Fall of 1942 Eddie was sent to the Pacific theater of war on a similar tour. He was also given a highly secret message by the Roosevelt Administration that was to be delivered personally to General Douglas MacArthur in Australia, supposedly a rebuke by President Roosevelt for negative comments that MacArthur had made about him. (The contents of that message from Roosevelt to General MacArthur have never been made public.)

General MacArthur, one of my long-time heroes, wasn’t the only one making negative comments about Roosevelt, who was a leftist/socialist member of what we today call “the Deep State” (and was a member of the treasonous Council on Foreign Relations). Rickenbacker also expressed negative public comments about Roosevelt. According to Wikipedia: “Eddie Rickenbacker was adamantly opposed to President Roosevelt’s “New Deal” policies, seeing them as little better than socialism. For this (affront to FDR) he drew criticism and ire from the press and the FDR administration, which ordered NBC Radio not to allow him (Rickenbacker) to broadcast opinions critical of Roosevelt’s policies….”

By October of 1942, Rickenbacker was on his way to the Pacific region. Dwight Zimmerman takes up the story at this point: “The trip was originally scheduled to begin on October 20, 1942, but Rickenbacker and the crew, led by pilot Capt. William Cherry, Jr., were delayed a day after being forced to transfer to another B-17 (aircraft) when their original aircraft suffered mechanical failure. At 1:30 a.m. on October 21, 1942, Rickenbacker, together with his aide, Col. Hans Adamson, and Sgt. Alexander Kaczmarczyk…took off from Hawaii for Canton Island, an atoll about 1,600 miles southwest of Hawaii. Scheduled to arrive at 9:30 a.m., by 10:30 they had not spotted their destination. Believing they had overshot (Canton Island), radio calls to Canton for directions proved useless, as the station there did not have equipment to give navigational bearings.”

It seems obvious that either the navigation equipment on the B-17 was faulty, or the navigator made some serious errors, because it soon became clear that they were irrevocably lost, with their fuel almost gone. Eventually, with their fuel tanks on empty, they prepared for a landing in the ocean. Despite high wave conditions, Capt. Cherry was able to belly land the B-17 in a trough between waves. It stayed afloat long enough for Rickenbacker and the six man crew to exit out of their sinking B-17. Rickenbacker later admitted, “I can say frankly that all of us were so anxious to get away from the B-17 before she sank (that) we didn’t pay much attention to our rations. We had no water when we went off and we had no food.” They had only four oranges that Capt. Cherry had stuffed into his jacket.

Rickenbacker and the six crewmen exited the aircraft and got into three small life rafts. One crewman, Adamson, suffered a badly sprained back during the rough landing; radio operator Sgt. James Reynolds had bad cuts on his hands and head, and Sgt. Kaczmarczyk had swallowed a large amount of seawater which made him very sick. Dwight Zimmerman continues the harrowing story in the November 15, 2012 issue of Defensemedianetwork.com:

“Rickenbacker had managed to carry a 60 foot rope out of the B-17, and the men used it to secure the three rafts together. What happened next was a 24 day epic of survival. Jammed into rafts barely large enough to hold them, the men suffered extremes of broiling hot days and freezing nights. Seawater regularly sloshed into their craft, adding to their agony. Their weight plummeted, Rickenbacker ultimately lost 80 pounds. Sgt. Kaczmarczyk suffered a relapse. His condition worsened and on the 13th day he died and was buried at sea.

“Rickenbacker had been placed in charge of the oranges. He made them last six days. On the eighth day, they received a bit of luck when Rickenbackeer captured a sea gull that landed on his head. The men feasted on the raw flesh and bones. The intestines were used as bait for the fishing lines and hooks stored in the life rafts. They got much needed water from a (rain) squall…. The stress of their situation saw morale…plummet. Keeping everyone’s spirits up became Rickenbacker’s main task.”

Search aircraft were spotted by the men on the 17th, 18th, and 19th days of total misery floating in the Pacific Ocean, but despite their efforts to attract the attention of the pilots searching for them, none of the searchers saw the men, who were desperate by this time. On the 20th day of their mutual ordeal, the majority decided that they would have a better chance of being spotted and rescued if they split up into three groups, which they did, despite Rickenbacker’s initial reluctance. Rickenbacker was left with his injured aide, Adamson, and a semi-conscious engineer, Pvt. John Bartek.

Finally, on the afternoon of day 24 floating at sea, a “Kingfisher OS2U” search aircraft found Rickenbacker’s raft, although it was dark before the search plane (which was a seaplane capable of landing on the ocean), rescued them. The men in the other two rafts were also soon rescued, ending their terrible ordeals, all of them suffering from bad sunburn, severe dehydration, and near starvation. (Interestingly, the military had decided to discontinue its search for Rickenbacker and the others almost a week BEFORE they were found, but had agree to search for another week at the strong urging of Rickenbacker’s wife!) After recovering in a military hospital, Rickenbacker resumed his original mission, delivered the secret message to General MacArthur, and returned home to the U.S.

That’s not the end of the Rickenbacker saga. Wikipedia tells us, “Rickenbacker supported the war effort as a civilian. Initially he supported the “isolation movement” (the America First Organization also supported by Charles Lindbergh at the time), but he officially left that group in 1940 after membership of only a few months. Afterwards he strongly supported England and was inspired by “England’s heroic resistance to relentless air attacks from the German Luftwaffe.” He did his best to rally his fellow World War 1 vets to the British cause long before the attack on Pearl Harbor.”

In 1943, with the permission of the U.S. government, Rickenbacker went to the Soviet Union to aid that beleaguered country (that had been invaded by the Nazi forces) with their American-built aircraft (many were P-39 Air Cobras) and assess their military capabilities for our military. Eddie was greatly respected by the Soviet high command, and he made recommendations regarding the aircraft that the U.S. government had provided through the Lend Lease program. He was also taken on a tour of an Ilyushin (Soviet bomber) factory. Rickenbacker completed his mission successfully, but his reputation was temporarily marred over his inadvertent error (a “slip of the tongue”, we assume) in alerting the Soviets to the top secret B-29 Superfortress project that was ongoing at the time.

At the conclusion of World War 11, Eddie Rickenbacker resumed the Presidency of Eastern Airlines. Unfortunately, his company’s success began to erode due to several factors, one of which was his great reluctance to commit Eastern Airlines to buy and use the new jet passenger aircraft, a big mistake for certain. On October 1, 1959, he was forced out of his position as CEO of Eastern Airlines, although he did stay on as Chairman of the Board until December 31, 1963. At age 73 he and his wife began to travel around the world, enjoying retirement as well as possible. Edward Rickenbacker, one of the heroes of my youth, passed away in Zurich, Switzerland on July 27, 1973, after suffering a severe stroke. He was one of many heroes who did his part to resist the enemies of his nation, and was a worthy example to patriots fighting our own domestic enemies today. I believe that history’s conclusion regarding Rickenbacker will always be: Well done, good and faithful patriot!