BOSTON: THE SEEDBED OF ANTI-BRITISH SENTIMENT

I’ve been to Boston, Massachusetts several times, and aside from the horrid traffic, I’ve thoroughly enjoyed each visit. Great food, especially at the venerable Union Oyster House and the now defunct Durgin Park restaurant, and lots of one of my favorite subjects: History. My wife and I have walked “The Freedom Trail” through Boston several times (the last two visits with our family), and each of our “treks through history” has taken us to OldGranary Burial Ground, which is full of the graves of the famous (Paul Revere, John Hancock, Sam Adams, James Otis, Mary (not Mother) Goose, Benjamin Franklin’s parents, Robert Treat Paine), and the not-so- famous of our early history. One grave marker in that ancient cemetery has always intrigued me, for carved on it are the names of five people whose deaths have been well documented in history. They are the five Bostonians who were killed by British soldiers during the infamous “Boston Massacre” on March 5, 1770, which occurred in front of the Old Statehouse Building: (Samuel Gray, Samuel Maverick, James Caldwell, Crispus Attucks, and Patrick Carr). I’ve stood on the exact spot where they died. It is the 6th person that usually eluded my attention, the death of whom might have been THE catalyst that eventually ignited our American Revolution.

(For my story, I’ve referred to and quoted freely from the following publications: Celebrate Boston, Find A Grave, Revolutionary War and Beyond, and “Christopher Seider” in Wikipedia. None of these publications had any author attributed to the articles, but I’ve used their research to amplify my own thoughts.)

Most students of American history have been taught that our glorious American Revolution (the first one) began with “the first shot” on Lexington Green in Massachusetts on the misty early morning of April 19, 1775. Others are certain that it began with The Boston Tea Party on Dec. 16, 1773. A few years ago I made the case, here in The Times Examiner, that “The Gaspee Affair” of June 9, 1772 (when H.M.S. Gaspee, a British war ship, tried to capture a colonial merchant smuggling ship, the Hannah, in Narragansett Bay, was lured into shallow water,; grounded, and burned by Rhode Island patriots, causing great indignation from the British government and great rejoicing among the colonies), could be THE “cause celebre” that pushed the colonies finally to separate from Britain.

Of course, there were two much earlier “incidents” which happened in that seedbed of revolution, Boston, that some are convinced were of sufficient magnitude to stir up such political umbrage among our hot- headed revolutionary ancestors as to virtually assure an eventual break with our “Mother Country”, Great Britain. One was called “The Boston Massacre”, which occurred on March 5, 1770. That event surely did ignite the passions of Bostonians virtually to the breaking point, killing five “stirred up” patriots and wounding several others. Had it not been for the cool headedness of two of our eventual “Founding Father” attorneys, John Adams and Josiah Quincy, Jr., who represented the British soldiers who fired into the crowd (they were arrested, and after a trial most were found “not guilty”--two were found ‘guilty’ and had their hands branded), the “first shots” of the American Revolution might have started after that trial.

11-YEAR-OLD CHRISTOPHER SEIDER KILLED ON FEB. 22, 1770

However, it is the story of the 6th name on that Old Granary grave marker that piqued my curiosity, for I had been mostly oblivious to his existence until recently. Could it be an almost forgotten fact of American history that the death of an eleven-year-old boy at the hands of a frightened Boston Loyalist was the “spark” that was to eventually cause such a conflagration of indignation and rebellion among our revolutionary ancestors as to virtually assure the Glorious Revolution? I believe that it was not only possible, but probable, that the death of a pre-teen boy who, for whatever reason, was caught up among the “rabble rousers” and “angry hotheads” in pre-Revolutionary Boston, DID ignite the first faint flash of resistance to tyranny that was to result in the defeat of the then mighty British Empire just thirteen years later.

The grave marker of Christopher Seider (his name-“Snider”-and his age-“12”-were carved incorrectly on the grave marker) proclaims him to be: “The innocent, first victim of the struggles between the Colonists and the Crown, which resulted in INDEPENDENCE.” So who was Christopher, and how did he lose his life in a mob on a crowded Boston street on Feb. 22, 1770, eleven days BEFORE the infamous Boston Massacre? Little is known of his life, and his story was almost lost to history and to the momentous events happening in the Colonies over the next decades . The boy was born to poor German immigrant parents sometime in 1758. At the time of his death at age 11 (some new sources indicate he may have only been 10 when he was killed), he lived in the home of a wealthy widow named Grizzell Apthorp, and worked for her as her servant boy.

YEARS 1767-1770—A POWDERKEG OF PASSIONS

By 1770, all the British American colonies were engaged in boycotts of various goods produced in Britain, as a protest of the despised Townshend Acts, which taxed many common items, including tea, and greatly increased the penalties for refusing to pay customs duties. Always looking out to make profits, British Loyalist merchants usually ignored the boycott of British-imported goods imposed by their fellows and would use the scarcity of necessary goods by continuing to import them and sell them to other Loyalists, an endeavor which thoroughly incensed hordes of Bostonians. One such Loyalist was an elderly man named Theophilus Lillie (1685-1776), who was the proprietor of a dry goods and grocery store that had been started by his wife, Hannah (who died in 1767), or her family, in Boston’s North End (where Paul Revere lived).

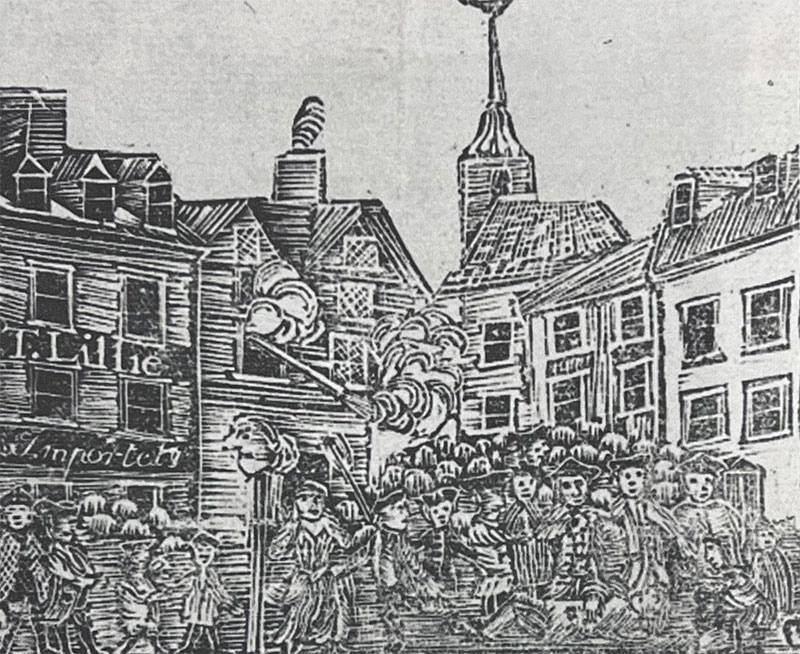

From the historical record, it appears that Mr. Lillie, a well known breaker of the boycott of British goods, endured a protest outside of his store on Feb. 22, 1770, as Bostonians tried their best to shame him and all of his customers over their support of the acts of a tyrannical parliament 3000 miles away. History students will recall that at the end of The French and Indian War (1763), the British Parliament enacted a series of taxes that would force the colonies to pay for the large costs of protecting them and winning that war. We know that the colonists considered these taxes to be unjust, and they became totally unpopular. In Massachusetts, and especially in and around Boston, resistance to these hated taxes took the form of frequent public protests and angry and unruly confrontations with tax collectors.

Making matters worse, in 1768 Governor Francis Bernard, fearing increased public unrest, requested the British government to send him 4,000 troops to keep order, mostly in and around Boston. Lacking sufficient barracks space for this large number of British troops, the Governor forced the colonists to provide quarters for them in their OWN HOMES, which infuriated the Bostonians. A new “resistance” group, which began calling itself The Sons of Liberty, was formed to oppose this attack on the colonists’ freedoms, adding more fuel to the incipient fires of rebellion.

It was into this powder keg of increasing mob hostility and very divided loyalties that Theophilus Lillie, a native-born Bostonian, began to ignore the colonists’ demands to boycott British taxable goods, claiming he “would rather be ruled by a single tyrant than by a mob of tyrants”. Thus it was that on Feb. 22, 1770, a sizeable number of Bostonians gathered outside his shop to protest his lack of support for their boycott. The Loyalists had previously responded to these protests by demanding that the Governor station British troops throughout Boston to keep the peace and prevent damage. Often the colonists would throw snowballs, sticks, and even rocks at the soldiers, and sometimes engage them in fistfights. (These proto-Americans weren’t always ‘peaceful’, particularly in pre-Revolution days). Thus was the scene set for an event that probably influenced the course of American freedom.

PROTESTERS WERE ANGRY IN THOSE DAYS ALSO.

So come with me to Boston on February 22, 1770. The protagonists in this drama are a mob of angry and protesting Bostonians (sounds familiar, doesn’t it?), some number of British “peacekeeping” troops, a shop owner—Theophilus Lillie-- and an 11-year-old servant boy, Christopher Seider, who just happened to be in the wrong place at the wrong time, but who in the long annals of history, was in the “right” place to cause that historical timeline to veer off into a new direction.

Here we are---in front of Mr. Lillie’s shop on a chilly February day. Surrounding it are an increasingly angry mob of Boston hotheads (incited, without any doubt, by members of the local branch of The Sons of Liberty). Lillie is cowering in his store, the doors locked, praying that the few British troops watching the mob would protect him from the wrath of the angry Bostonians—his fellow townspeople who until recently had been his customers for the British goods he imported. Lillie, I’m sure, could feel the anger of the protesting mob, who took increasing umbrage over his and other Loyalist merchants’ refusal to support the boycott of various British goods, upon which Parliament had placed additional tariffs (taxes) to help pay for the large debts that had been incurred during the French and Indian War.

Mr. Lillie had a long record, the protesters believed, of pro-British, pro-tariff support. The historical record is a bit “murky” about that. The Sons of Liberty (probably) had previously erected a very unflattering effigy of Lillie outside of his store to warn would-be customers that he, Lillie, was a Loyalist to the Crown; hence it was considered to be unpatriotic to purchase goods from him, particularly goods imported from Britain.

It was into this angry and growing protest that Ebenezer Richardson (1718-?), an employee of the Crown’s Customs Office, came upon the protesting mob in front of Mr. Lillie’s store, a mob that was engaged in throwing stones at the store’s windows, a mob carrying many anti-British protest signs. Unfortunately for Richardson, he was already a known and hated British Loyalist himself, having on previous occasions informed the Governor’s Attorney General of the activities of the patriots of Boston (he was a known “snitch”). The angry crowd soon recognized Richardson and turned their wrath upon him, and began throwing stones at him, at least one of which struck his head. The totally frightened Richardson retreated from the melee and ran to his nearby home, with the angry mob chasing him. He barricaded himself in his house, while the mob outside pelted his house with rocks.

As “fate” would decree, it was just at this time that young Christopher Seider was returning to the Widow Apthorp’s home, and he came upon (and some witnesses claimed he ‘joined’) the angry mob of his fellow citizens. Rocks thrown by the protesters broke many of Richardson’s windows, and his wife was struck by one of the stones. Mr. Richardson later claimed that he “panicked” and, fearing for his and his wife’s lives, he loaded one or more of his muskets and began to fire through his broken windows into the crowd. Sadly, 11-year-old Christopher, who had entered a momentous and perhaps decisive moment in time, was struck by Richardson’s musket fire in his chest. He died later that evening, never realizing that his death may have precipitated the American Revolution just a little over five years later.

Mr. Richardson’s defense of his home and life and his wife also wounded several other protesters, which so infuriated the mob that he and his wife had to be rescued by a squad of nearby British solders and taken into custody. Samuel Adams, an eventual “Founding Father” of the U.S., arranged Christopher’s funeral, and over 2000 Bostonians attended. This killing of 11-year-old Christopher Seider, plus his large public funeral, completely outraged the people of Boston, reaching its peak just eleven days later, when a squad of British soldiers was harassed and threatened by another angry mob of protesting patriots, thereby causing what was called the infamous “Boston Massacre” right in front of the Boston State House.

Ebenezer Richardson was eventually tried for the murder of the young boy and was found guilty, and ordered to be executed. But his execution was overturned. Instead, he served two years in prison and was then pardoned by the Royal Governor, who declared that he had acted in defense of his and his wife’s lives. He was given a promotion in the British Customs Service. This tragic event, however, became just another “thorn” in the flesh of Bostonians who were piling up “grievances” against the British Crown (which they eventually listed in our “Declaration of Independence” in 1776).

On the day of Christoher’s funeral a huge parade formed, from the “Liberty Tree” to the Granary Burial Ground. Posters were distributed all over Boston that demanded that his death be avenged. The March 2, 1770 issue of the New Hampshire Gazette, described the public outrage over young Seider’s death:

“This innocent lad is the first, whose LIFE has been a victim to the cruelty and rage of Oppressors! Young as he was, he died in his country’s cause, by the hand of an execrable villain, directed by others, who could not bear to see the enemies of America made the ridicule of boys. The untimely death of this amiable youth will be a standing monument to futurity, there the time has been when innocence itself was not safe! The blood of you, Alien, may be covered in Britain: But a thorough inquisition will be made in America for that of young Seider, which crieth for vengeance, like the blood of righteous Abel. And surely, if justice has not been driven from its seat, speedy vengeance awaits his murderers and their accomplices, however secure they may think themselves present. For those who sheddeth, or procureth the shedding of Man’s Blood, by Man shall his blood be shed.”

A beautiful velvet “pall”, or covering, was placed over Christopher’s coffin, with Latin words on it that said: The serpent is lurking in the grass. The fatal dirt is thrown. Innocence is nowhere safe.”

Just eleven days later, the “Boston Massacre” occurred, during which five of Christopher’s fellow Bostonians were killed, and several others wounded. They were eventually buried together in the Old Granary Burial Ground, and I’ve stood before their grave marker several times. Now you know at least a little of the tragically short life story of 11-year-old Christopher Seider, who has often been called the “First Martyr of the American Revolution. Most Americans have forgotten, or truthfully, never knew his name. Even those who buried him misspelled his name and assigned him a wrong age on their joint grave marker.

If you ever go to Boston (and I hope that you will, if you haven’t already done so), be sure to go to the OLD GRANARY BURIAL GROUND, right next to the newer and beautiful Park Street Church. Stand in front of the grave marker of the five patriots who were killed during the Boston Massacre. And please notice the SIXTH name on the marker: Christopher Seider (misspelled ‘Snider’). Did his death really start the train of events that resulted in the Glorious American Revolution of 1775? I believe a good case can be made for that possibility, but ultimately “history” will proclaim its verdict!