Back in 1988, during one of our trips to Boston and vicinity, my wife and I went aboard the sailing brig, “Beaver”, a recreated ship of the type used back in the 1770’s. It was moored close to the site, in Boston Harbor, where the original “Boston Tea Party” was “held” back in 1773, during which The Sons of Liberty and their friends, dressed unconvincingly as “Indians”, dumped many chests of expensive, but “boycotted” tea, into the harbor. It must have been quite a sight, and it thoroughly incensed the British colonial government. On the recreated Beaver, there were several small chests of “pretend tea”, roped to the deck rail. My wife and I, and our daughter and her husband, thoroughly enjoyed our own version of “The Boston Tea Party”, as we threw those pretend tea chests into the harbor (several times, as I recall). It was a treat to “relive” history, and it was “liberating” to follow, if only figuratively, in the footsteps of patriots from an earlier time.

However, the patriotic “hornet’s nest” of Boston was not the only colonial city to hold a “tea party”. I was vaguely aware, historically, that there were multiple “tea parties” (the violent dump or burn the tea versions)—in fact there were SEVENTEEN recorded “tea parties” in the British colonies during the years leading up to our first American Revolution. Besides the most well known “Tea Party”, the one in Boston in 1773, there were also versions of them in Edenton and Wilmington, North Carolina, in New York, in Charleston, and in several other towns, including the one which could have rivaled the “affair” in Boston, the Annapolis, Maryland “Tea Party” of October 19, 1774, which was a bit more violent and destructive. That’s the one I’d like to tell you about.

(I’m indebted to the award winning Maryland author and blogger, Kate Dolan, for her great historical research and articles on the Annapolis “Tea Party”, and I’m quoting freely from two of her articles: The Peggy Stewart Affair: Maryland’s Flaming Tea Party, and Have We Forgotten?, from her blog of Oct. 19, 2017).

Over the past decade or two, Americans have resurrected a modern genre of the historic political “tea party” protest movement, a version of the colonial “Tea Party” phenomena that flashed like a meteor over Britain’s American colonies during the last half of the 1760’s and the first half of the 1770’s. Kate Dolan wrote: “The tea parties were part of a protest movement against British ‘taxation without representation’ that dated back to the imposition of the Stamp Act of 1765”. (Parliament’s way of paying for the huge expenses incurred during the French and Indian War—1756--1763). “In hindsight, the British probably should have simply given the colonies a representative in Parliament who would have been outvoted on everything. Then the (British) Americans would not have been able to back their protests with such moral fervor. But the British government took a stubborn stance against their obnoxious…colonies, and…the Americans reacted with a rebellious display of drama.”

Dolan continues: “…(T)he colonists involved in this (Annapolis) protest…acted in broad daylight and insisted on not only destruction of tea, but of the entire ship carrying it. Why didn’t the British close the port of Annapolis in response? Most likely they didn’t care. Private individuals owned both the ship and the tea. And by this time, so many locations were holding protests that this one may hardly have been noticeable.”

“It was a big deal in Annapolis, however, because it forced people to take sides. At issue was not only the question of whether the British government had the right to levy a direct tax on colonists or take control of colonial governments. Most were in agreement that the British had overstepped their boundaries. The bigger question was how far people were willing to go to assert their right to be free of this taxation and excessive control.” Wow, they should see us now, when excessive taxation and excessive control by all levels of government are endemic—and all WITH “representation”!

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND OF THIS AFFAIR

The British sailing brig, Good Intent, docked in Annapolis in February, 1770, ending her long voyage from London, and was carrying merchandise that Annapolis merchants had ordered a year earlier. At this point in time, a boycott of goods that were taxable to the colonists under the despised Townshend Acts of 1767 was in effect throughout the colonies. However, some of the goods on Good Intent were ordered before the local colonial resolutions (to boycott certain British goods) of early summer, 1769, went into effect. Thus, a “sticky situation” developed between these merchants and the colonial customs collector in Annapolis, who announced that he would refuse to allow ANY goods to be offloaded from the ship, even those that apparently were not subject to being taxed, until the taxes had been paid to his office.

Complicating the situation, the local Annapolis committee that oversaw compliance with the boycott of British goods would not permit taxes to be paid on any of the goods aboard Good Intent. After much heated arguing, the Annapolis merchants capitulated to the will of their fellow townspeople, and two of the prominent importers of British goods, James Dick and his son-in-law, Anthony Stewart, ordered Good Intent to return to London with all of her cargo still aboard. In an ironic twist, this ship was in the middle of its voyage back to London when Parliament finally relented to the colonists’ boycott, and removed its taxes on all imported British goods—ALL except tea!

Three years later, the Tea Act of 1773 was passed by the British Parliament, but it authorized ONLY one firm, the British East India Company, to market its tea in the British colonies without paying any tax on it. This “arrangement” was deemed to be as unjust and unacceptable to the colonists as the taxes imposed by the despised Townshend Acts had been. The “umbrage” caused by The 1773 Tea Act finally led, as we know, to the famous “Tea Party of 1773” held in Boston. Parliament, unfortunately, reacted harshly and this led to the reintroduction of the tea (and other British imports) boycotts.

THE PEGGY STEWART “TEA PARTY”

The years 1773 and 1774 saw many versions of “tea party” protests by the British American colonists. Kate Dolan picks up the story: “The ‘Peggy Stewart’ was a small merchant vessel owned by Anthony Stewart and his father-in-law, James Dick.” (The same merchants who had tried to import boycotted goods into Annapolis four years earlier). “In London, representatives from a rival merchant firm loaded tea on the ‘Peggy Stewart’ but allegedly told (its’ captain) that the packages contained linen. The captain suspected otherwise and just before (he) sailed, customs documents revealed that the packages…contained tea. Maryland colonists…were boycotting British tea to protest the taxation and the British (government’s) treatment of Boston. So when the ship reached Annapolis, the captain knew there would be trouble.” And there was, with a capital “T”!

According to research by Kate Dolan, the ‘Peggy Stewart’ was named after Anthony Stewart’s daughter, Margaret. Dolan writes: “The ‘Peggy Stewart’ had numerous problems and contraband tea was only one of them. The ship leaked badly and barely made it across the Atlantic. And the main cargo consisted of 53 indentured servants sold into service in the colonies. Once the leaking vessel arrived in Annapolis, no cargo could be removed until the tax on the tea was paid (and) the indentured servants were considered “cargo”. The vessel was not likely to survive another Atlantic crossing—in fact it was in danger of sinking right in the harbor. So feeling that he had no choice,…Stewart paid the tax.”

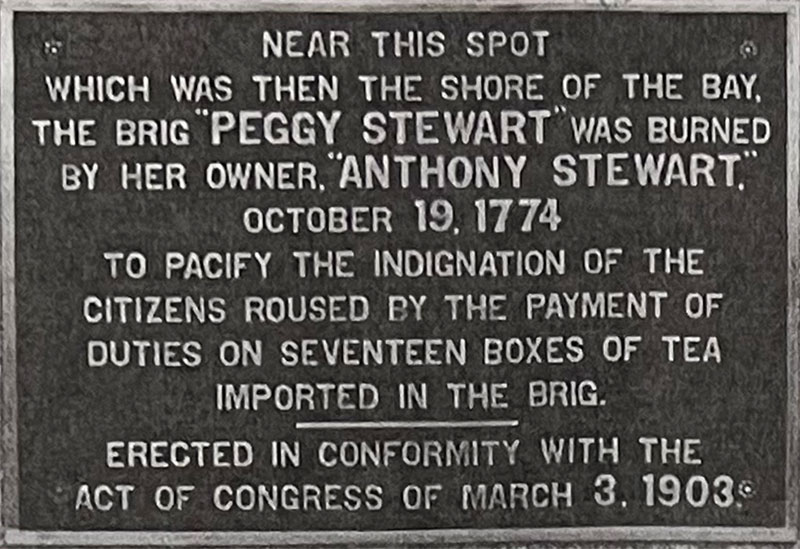

There are conflicting accounts about the events that followed Stewart’s payment of the hated tax. According to Dolan, “This made him an enemy to every patriot in town, or at least the “grab your torch and pitchfork” variety that fueled their righteous anger with spirits and rhetoric…. After several days of negotiation, Stewart agreed to sign a paper stating he had behaved wrongfully and that the tea should be burned.” One account claims that most of the colonists in Annapolis believed that offloading and burning the taxed tea was sufficient and would end this particular matter. However, not all of the colonists were satisfied by Stewart’s groveling “compromise”. A group of “radicals”, led by Matthias and Rezin Hammond, led what became a “mob” right to Stewart’s home. They brazenly built a gallows in front of it, then began calling for the burning of his house and the tarring, feathering, and hanging of Stewart if he didn’t agree to burn his own ship, the ‘Peggy Stewart’! Faced with poor choices, Stewart and two associates were rowed out to his crippled and controversial ship. History hasn’t recorded Stewart’s feelings as he and the other two men set fire to his ship, with ALL 2320 pounds of the offending and boycotted tea still aboard (the indentured men had already been removed from the ship). The large crowd cheered loudly as ‘Peggy Stewart’, with all her sails hoisted and the British Union Jack flying, burned to its waterline and finally sank. Afterward, the now notorious Stewart and his family felt unwelcome in Annapolis and soon left for London, later relocating to Nova Scotia where many Tories resettled during and after the Revolutionary War.

The “Peggy Stewart Tea Party” was but one of many on the Colonists’ road to rebellion and ultimate separation from Mother England. It was EXACTLY six months to the day after this ‘affair’ that the first shots of our glorious War of the Revolution were fired in Lexington and Concord. Unfortunately, because of this Annapolis ‘tea party’, Stewart’s father-in-law, James Dick, was financially ruined, spending the rest of his life holed up in his Annapolis home, and was called “The Old Tory” by the townspeople. He had made his decision, and the townspeople had made theirs, decisions that resulted eventually in the birth of the U.S.A.