Topline Preliminary Estimates

| 11-Year Revenue (Trillions) | Long-run GDP | Long-Run Wages | Long-Run FTE Jobs |

|---|---|---|---|

+$2.2T |

-2.2% |

-1.6% |

-788k |

Source: Tax Foundation General Equilibrium Model, March 2024.

President Biden’s State of the Union address presented a vision of higher taxes for American businesses and high earners combined with carveouts, credits, and more complex rules for taxpayers at all income levels. Soon after, the president released his FY 2025 budget outlining how the White House would implement the president’s tax vision, indicating a gross tax hike of about $5.3 trillion from 2024 to 2034.

On a gross basis, we estimate Biden’s FY 2025 budget would increase taxes by about $4.4 trillion over that period. After taking various credits into account, the increase would be about $3.4 trillion. The tax increases would substantially increase marginal tax rates on investment, saving, and work, reducing economic output by 2.2 percent in the long run, wages by 1.6 percent, and employment by 788,000 full-time equivalent jobs.

The tax changes Biden proposes fall under three main categories: additional taxes on high earners, higher taxes on U.S. businesses—including increasing taxes that Biden enacted with the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA)—and more tax credits for a variety of taxpayers and activities. The combination of policies would move the tax code further away from simplicity, transparency, and neutrality, while making the U.S. economy less competitive. The increase in the corporate tax rate and the additional taxes on top earners would result in U.S. top marginal tax rates on income that are among the highest in the developed world.

Long-Run Economic Effects of President Biden’s FY 2025 Budget

We estimate the tax changes in the president’s budget would reduce long-run GDP by 2.2 percent, the capital stock by 3.8 percent, wages by 1.6 percent, and employment by about 788,000 full-time equivalent jobs. The budget would decrease American incomes (as measured by gross national product, or GNP) by 1.9 percent in the long run, reflecting offsetting effects of increased taxes and reduced deficits, as debt reduction reduces interest payments to foreign owners of the national debt.

Raising the corporate income tax rate to 28 percent is the largest driver of the negative effects, reducing long-run GDP by 0.9 percent, the capital stock by 1.7 percent, wages by 0.8 percent, and full-time equivalent jobs by 192,000.

Our economic estimates likely understate the effects of the budget since they exclude two novel and highly uncertain yet large tax increases on high earners and multinational corporations, namely a new minimum tax on unrealized capital gains and an undertaxed profits rule (UTPR) consistent with the OECD/G20 global minimum tax model rules. Nor do we include the budget’s unspecified research and development (R&D) incentives that would replace the lower tax rate on foreign-derived intangible income (FDII).

Table 1. Long-Run Economic Effects of President Biden’s FY 2025 Budget

| Gross Domestic Product (GDP) | -2.2% |

| Gross National Product (GNP) | -1.9% |

| Capital Stock | -3.8% |

| Wage Rate | -1.6% |

| Full-Time Equivalent Jobs | -788,000 |

The budget would include the following major changes, beginning in 2025, unless otherwise noted.

Major business provisions modeled:

- Increase the corporate income tax rate from 21 percent to 28 percent (effective 2024)

- Increase the corporate alternative minimum tax introduced in the Inflation Reduction Act from 15 percent to 21 percent (effective 2024)

- Quadruple the stock buyback tax implemented in the Inflation Reduction Act from 1 percent to 4 percent (effective 2024)

- Make permanent the excess business loss limitation for pass-through businesses

- Further limit the deductibility of employee compensation under Section 162(m)

- Increase the global intangible low-taxed income (GILTI) tax rate from 10.5 percent to 21 percent, calculate the tax on a jurisdiction-by-jurisdiction basis, and revise related rules (some provisions effective 2024)

- Repeal the reduced tax rate on foreign-derived intangible income (FDII)

Major individual, capital gains, and estate tax provisions modeled:

- Expand the base of the net investment income tax (NIIT) to include nonpassive business income and increase the rates for the NIIT and the additional Medicare tax to reach 5 percent on income above $400,000 (effective 2024)

- Increase top individual income tax rate to 39.6 percent on income above $400,000 for single filers and $450,000 for joint filers (effective 2024)

- Tax long-term capital gains and qualified dividends at ordinary income tax rates for taxable income above $1 million and tax unrealized capital gains at death above a $5 million exemption ($10 million for joint filers)

- Limit retirement account contributions for high-income taxpayers with large individual retirement account (IRA) balances

- Tighten rules related to the estate tax

- Tax carried interest as ordinary income for people earning more than $400,000

- Limit 1031 like-kind exchanges to $500,000 in gains

Major tax credit provisions modeled:

- Extend the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) child tax credit (CTC) through 2025 and make the CTC fully refundable on a permanent basis (effective 2024)

- Permanently extend the ARPA earned income tax credit (EITC) expansion for workers without qualifying children (effective 2024)

We also modeled various miscellaneous provisions for corporations, pass-through businesses, and individuals, including several energy-related tax hikes largely pertaining to fossil fuel production. While the budget improperly characterizes fossil fuel provisions as subsidies, many are deductions for costs (or approximations of costs) incurred.

Major provisions not modeled:

- Repeal the base erosion and anti-abuse tax (BEAT) and replace it with an undertaxed profits rule (UTPR) consistent with the OECD/G20 global minimum tax model rules

- Replace FDII with unspecified R&D incentives

- Create a 25 percent “billionaire minimum tax” to tax unrealized capital gains of high-net-worth taxpayers

- Permanently extend the ARPA premium tax credits (PTCs) expansion (we do include PTCs in our distributional analysis)

- Expand federal rules on drug pricing provisions

- Spending program changes

- Provide additional Internal Revenue Service (IRS) funding

Table 2. Detailed Economic Effects of President Biden’s FY 2025 Budget

Source: Tax Foundation General Equilibrium Model, March 2024.Revenue Effects of President Biden’s FY 2025 Budget

The budget covers the 10-year period from 2025 through 2034, but also proposes tax increases and credits starting in 2024. As such, we present a revenue table below that includes the revenue change over the traditional 10-year budget window and the full 11-year period including 2024. We refer to the score over the full 11-year period throughout.

Across the major provisions modeled by Tax Foundation, we estimate the budget raises $2.2 trillion of tax revenue from corporations and $1.4 trillion from individuals from 2024 through 2034. We relied on estimates from the White House Office of Management and Budget (OMB) for provisions we did not model, including the billionaire minimum tax, UTPR, various international tax changes for oil and gas companies, smaller international tax changes, improvements to tax compliance and administration, and unspecified R&D incentives to replace FDII.

In total, accounting for all provisions, including those estimated by OMB, we estimate the budget raises nearly $4.4 trillion in gross revenue from tax changes over the 11-year budget window.

Expanded tax credits and the unspecified incentive to replace FDII reduce the gross revenue by $876 billion and $118 billion, resulting in a net tax increase of $3.4 trillion.

Outside of tax changes, the budget includes additional spending increases and cost savings including expanding the drug pricing provisions passed in the Inflation Reduction Act for a net increase in spending of $1.2 trillion, summarized in Table 3.

After accounting for all changes in revenue and spending, we estimate the net effect of the budget would be to reduce the deficit by nearly $2.2 trillion through 2034 on a conventional basis. On a dynamic basis, factoring in reduced tax revenues resulting from the smaller economy, the deficit reduction drops to $1.4 trillion.

However, the projected decrease in budget deficits is highly uncertain. About $742 billion of the increased revenue comes from untested sources—the 25 percent minimum tax on high earners and the UTPR.

The 25 percent minimum tax on unrealized capital gains has several novel features and would for the first time attempt to collect tax on a broad set of assets on a mark-to-market basis or on imputed returns, i.e., without a clear market transaction to firmly establish any capital gain or loss. It would apply to taxpayers with wealth greater than $100 million, requiring a new annual wealth reporting system.

It is unclear how many taxpayers would be subject to the reporting requirements and liable for the tax, or how taxpayers would react to such a regime. Based on the OMB estimate (converted to calendar years), the minimum tax would raise about $517 billion, though it is unclear what OMB assumed regarding avoidance behavior, valuation disputes, and other factors that could dramatically change this result.

Another highly uncertain minimum tax proposed in the budget is a UTPR and other provisions intended to align with the OECD/G20 global minimum tax model rules applicable to corporate profits earned internationally. Several countries are in the process of implementing global minimum tax rules including a UTPR, though our analysis and that of the Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT) indicate a great deal of uncertainty in forecasting how the rules will ultimately evolve across the globe.

Additionally, the JCT finds much uncertainty in estimating revenue effects of a potential UTPR in the U.S., ranging from a loss of $57 billion over a decade to a gain of $237 billion, depending on how other countries implement their rules. The OMB estimates the UTPR would raise about $140 billion over the budget window, which is about a quarter of what was predicted in last year’s budget. OMB estimates another $85 billion would come from disallowing foreign tax credits for oil and gas companies and other sundry tax increases.

The budget discusses additional policies that would significantly reduce revenue, such as extending tax changes from the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) for people making below $400,000 after 2025 when they otherwise expire. The budget does not, however, factor in the cost of such an extension. Similarly, the budget extends the larger CTC through 2025, but further extending the policy would cost more than $130 billion per year, adding more than $1 trillion to the deficit by 2033. Continuing both of the policies past 2025 would wipe out most, if not all, of the budget’s projected deficit savings.

Table 3. Additional Net Spending in President Biden’s FY 2025 Budget

Source: Budget of the U.S. Government Fiscal Year 2025; Tax Foundation General Equilibrium Model. Note: negative signs denote a net increase in the federal budget deficit, while positive values indicate a net decrease in the federal budget deficit.Table 4. Revenue Effects of President Biden’s FY 2025 Budget

*Note: "Miscellanious tax increases on saving include changes to tax rules on digital assets and a new tax on electricity consumption when mining digital assets.**Note: "Miscellanious passthrough tax increases include rules changing depreciation deduction recapture for real estate transactions and limitations on basis shifting for partnerships.

***Note: "Miscellanious tax increases on corporations include increased taxes on fossil fuel production, changes to REIT taxes, new rules for corporate affiliation tests, changes to corporate aviation taxes, and taxing certain corproate distributions as dividends.

**** Note: The Treasury Greenbook for FY 2025 proposes using the revenue from repealing FDII to "incentivize R&D in the United States more directly and effectively," and leaves the question of whether it is a tax or spending incentive ambiguous.

*****Note: Our estimates of permanent refundability for the Child Tax Credit do not incorporate a revenue effect for nonfilers.

*****Note: "Miscellanious tax credits include changes to the the adoption tax credit, tax exclusion for student loan income, tax credits for homebuyersn and home sellers, the neighborhood homes tax credit, the low income housing tax credit, the new markets tax credit, tax-preferred treatment to certain Federal and tribal scholarship and education loan programs, the work opportunity tax credit, and the employer-sponsored tax credit for childcare.

Source: Budget of the U.S. Government Fiscal Year 2025, Tax Foundation General Equilibrium Model, March 2024.

Distributional Effects of President Biden’s FY 2025 Budget

The budget would raise marginal income tax rates faced by higher earners and corporations while expanding tax credits for lower-income households. Our modeling of the distributional effects on after-tax income does not include the impact of drug pricing provisions, the 25 percent billionaire minimum tax, the undertaxed profits rule, miscellaneous tax credits, IRS enforcement, or spending program changes.

The budget would redistribute income from high earners to low earners. The bottom 60 percent of earners would see increases in after-tax income in 2025, while the top 40 percent of earners would see decreases. After-tax income for the bottom quintile would increase by 16.1 percent, largely from expanded tax credits. In contrast, the top 1 percent of earners would experience a 8.7 percent decrease in after-tax income.

After the expanded CTC expires, the bottom quintile would see a smaller 5.8 percent increase in after-tax income in 2034 on a conventional basis while the top three quintiles would see decreases in their after-tax incomes. The top 1 percent would see a 6.5 percent decrease in after-tax income.

On a long-term dynamic basis, the smaller economy reduces after-tax incomes relative to the conventional analysis. On average, tax filers in the top four quintiles would experience a drop in after-tax incomes, while the bottom quintile would still see an increase, albeit reduced to 3.7 percent, driven by the permanent changes to the CTC, EITC, and PTC.

Table 5. Distributional Effects of Tax Changes in President Biden’s FY 2025 Budget (Percent Change in After-Tax Income)

Note: We do not model the distribution of miscellaneous tax credits or unmodeled provisions listed above unless otherwise noted.Source: Tax Foundation General Equilibrium Model, March 2024. Items may not sum due to rounding.

Top Tax Rates Under President Biden’s FY 2025 Budget

President Biden’s budget proposals would raise top tax rates on corporate income, capital gains income, and individual income to levels that are out of step with the rest of the world.

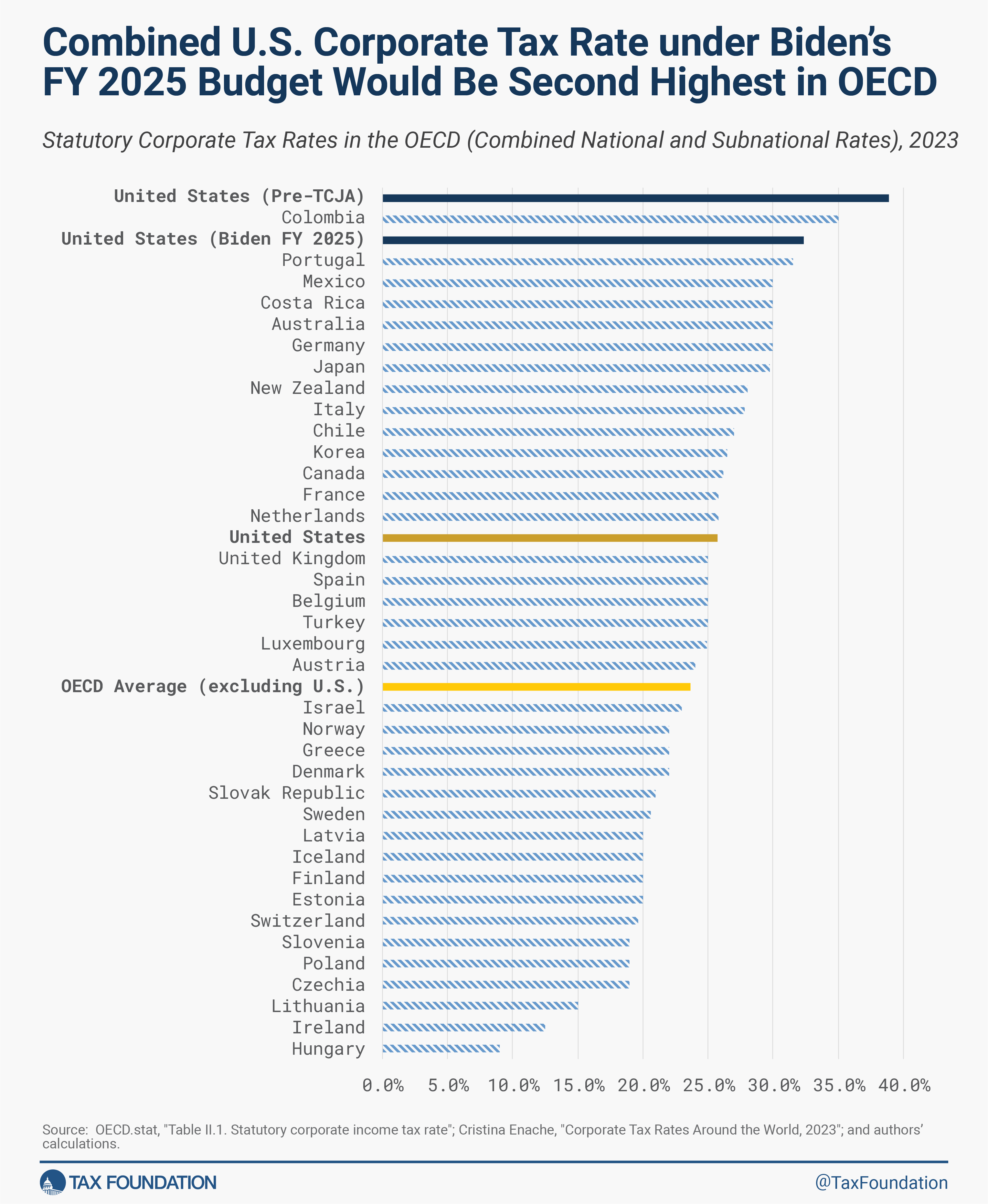

Raising the corporate income tax rates from 21 percent to 28 percent, a policy Biden has pushed for since the 2020 campaign, would significantly worsen the competitive position of U.S. businesses and reduce prospects for business investment and workers. Including the average of state rates, the top combined marginal rate on corporate income under current law is 25.6 percent, and Biden’s proposal would increase it to 32.2 percent—the second highest corporate tax rate in the OECD (behind Colombia at 35 percent).

The corporate income tax is the most harmful tax for economic growth and its many problems have led countries around the world to reduce corporate tax rates considerably over the last 40 years to an average of about 23 percent as of 2023. The U.S. had the highest corporate tax rate in the OECD prior to the TCJA, which lowered the U.S. corporate tax rate to be roughly average among OECD countries. Recent studies have determined that lowering the corporate tax rate significantly boosted investment in the United States, a long-term process that continues to yield economic benefits, including gains in workers’ wages.

On top of a higher statutory corporate tax rate, Biden has proposed increasing the rate of the new corporate alternative minimum tax on book income from 15 percent to 21 percent. The tax was enacted in August 2022 as part of the IRA and scheduled to go into effect starting in 2023, but the IRS postponed its implementation because of the complexity of enforcing it. Taxpayers are still awaiting guidance on several significant questions related to the CAMT, and it remains questionable whether the tax is even feasible. It has certainly failed thus far as an effective minimum tax.

Biden also proposes quadrupling the IRA’s 1 percent excise tax on stock buybacks. Stock buybacks are one of the ways businesses return value to their shareholders. Companies can return earnings to shareholders by issuing dividends (namely cash payments) or with stock buybacks (purchasing shares of their own company). As much as 95 percent of the money returned to shareholders from stock buybacks subsequently gets reinvested in other public companies. Quadrupling the tax rate would likely discourage firms from pursuing stock buybacks, potentially tilting toward more dividend issuances instead, and could discourage investment.

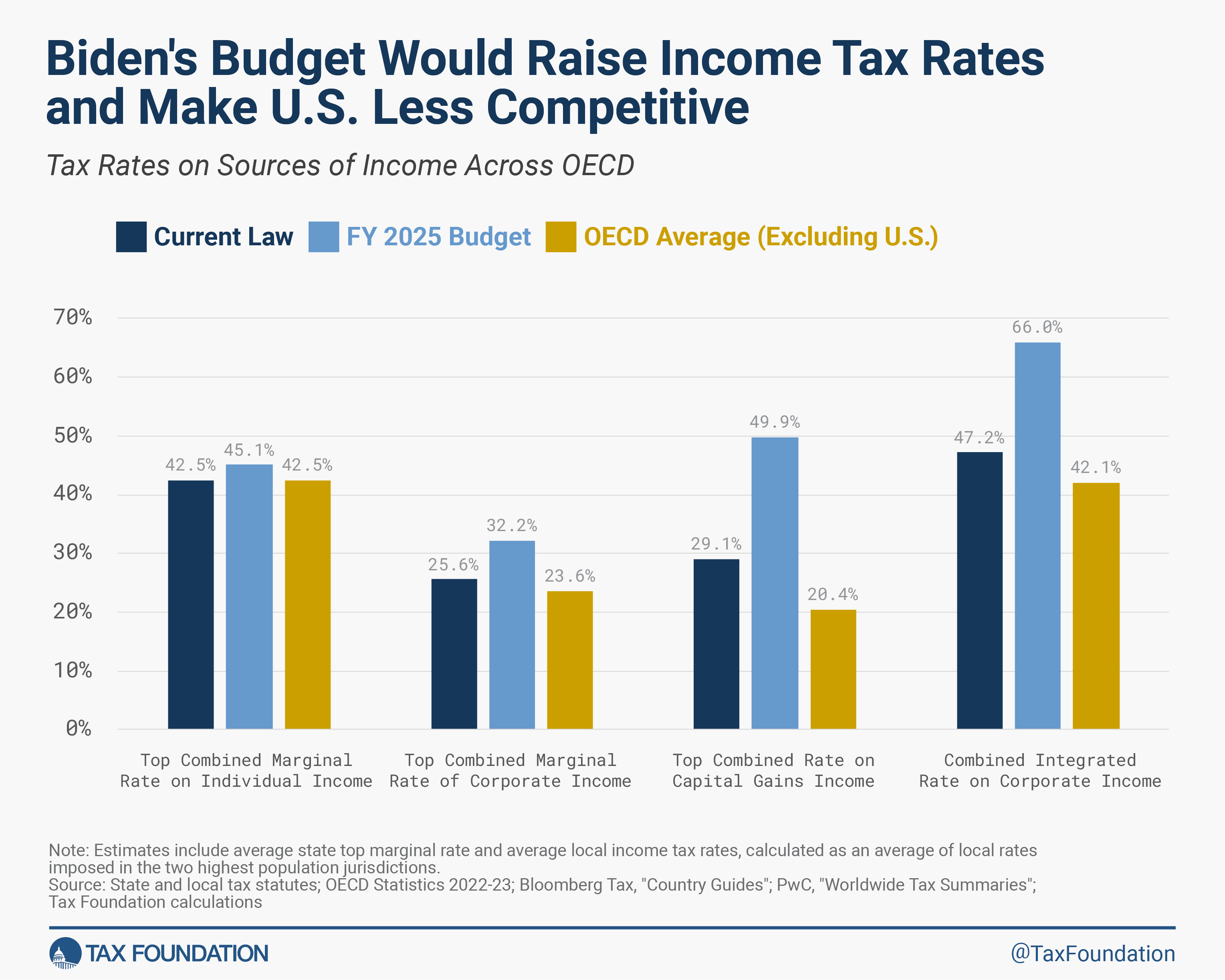

On personal income taxes, too, the Biden budget proposals would further push up marginal tax rates. Under current law, the top combined marginal tax rate on individual income is 42.5 percent, consisting of the top federal rate (37 percent) and the average of state and local income tax rates. Biden’s proposal would raise it to 45.1 percent by increasing the top rate from 37 percent to 39.6 percent. The rate ignores the 5 percent additional Medicare tax, half of which falls on the employer, in order to make comparisons to the personal income tax regimes in the OECD database. Including the employee-side portion of this tax would raise the top rate to 47.6 percent.

In the case of capital gains taxes in particular, the changes would push the United States beyond international norms. The top combined marginal tax rate on capital gains income under current law is 29.1 percent, consisting of the 20 percent capital gains tax rate, the 3.8 percent net investment income tax (NIIT), and the average of state and local income tax rates on capital gains. By taxing high earners’ capitals gains as ordinary income and raising the NIIT to 5 percent, Biden’s proposals would raise the top tax rate on capital gains to 49.9 percent—the highest in the OECD.

Aiming to address Medicare’s growing budgetary shortfalls, the president would raise the hospital insurance (HI) payroll tax for people earning more than $400,000 from 0.9 percent to 2.1 percent, expand the base of the NIIT to include active business income, and raise the NIIT to 5 percent for high earners. The changes would raise top tax rates on labor, investment, and business income while not doing enough to put entitlements on a path toward solvency.

The combined integrated rate on corporate income reflects the two layers of tax corporate income faces: first at the entity level through corporate taxes and again at the shareholder level through capital gains and dividends taxes. Under current law, the top combined integrated tax rate on corporate income distributed as capital gains is 47.2 percent. Under Biden’s proposals, it would rise to a jaw-dropping 66 percent—the highest in the OECD.

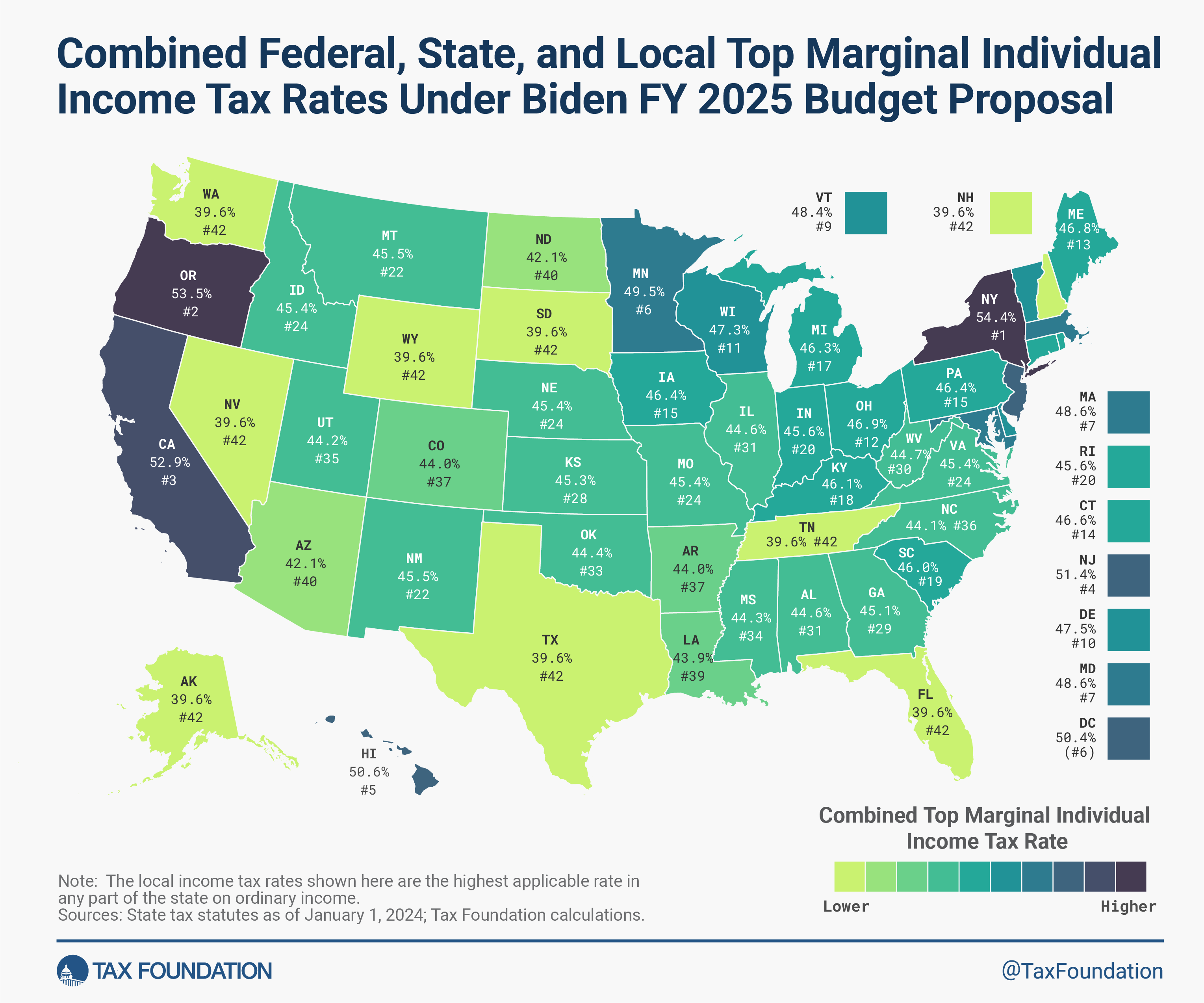

Biden’s FY 2025 budget would yield combined top marginal rates on individual income in excess of 50 percent in five states and D.C.: New York (54.4 percent), Oregon (53.5 percent), California (52.9 percent), New Jersey (51.4 percent), Hawaii (50.4 percent), and D.C. (50.4 percent).

Additionally, President Biden reintroduced his proposal to raise the effective tax rates paid by households with net worth over $100 million. The proposal requires high net worth households to pay a 25 percent minimum tax rate on an expanded definition of income that includes unrealized capital gains. Under the minimum tax, households would pay tax on capital gains even if the underlying asset has not yet been sold, operating as a prepayment for future capital gains tax liability.

The billionaire minimum tax, as it is commonly known, would increase the complexity of the tax code by using a non-traditional and difficult-to-measure definition of income. It would require formulaic rules for valuing different types of assets, payment periods that vary by asset type, and a separate tax system to deal with illiquid assets. This tax design goes well beyond international norms, where capital gains are taxed when realized and at lower rates than the U.S. in many cases.

Biden would also expand the disallowance of deductions for employee compensation above $1 million (Section 162m) to cover all employees of C corporations. The cap currently applies to the CEO, CFO, and the next three highest-paid employees of a corporation, and due to ARPA is already scheduled to expand to the next five additional highest-paid employees beginning after 2026.

Expanding the disallowance makes it costlier for corporations to attract and retain top talent. It would mean both the corporate and individual top tax rates would apply to wages, resulting in top tax rates of 70 percent or more including state taxes. If the $1 million threshold is not indexed to inflation, over time the tax would hit more than just the C-suite.

Other Provisions

Seeking to address the very real problem of housing affordability, Biden has called for several proposals to subsidize home purchases and boost the low-income housing tax credit, including a tax credit worth $5,000 per year for two years for middle-class, first-time homebuyers. The president would also offer a one-year tax credit worth up to $10,000 for middle-class households who sell a starter home to help improve starter home availability. Finally, the president proposes to provide up to $25,000 in down payment assistance for first-generation homebuyers.

Boosting demand through subsidies is likely to cause housing prices to increase further. What is needed is a greater supply of housing, which would be best accomplished at the state and local level by reforming zoning rules and at the federal level by reforming tax depreciation rules for residential structures.

For developers, the president would expand the low-income housing tax credit (LIHTC) and create a new neighborhood homes tax credit to build or renovate affordable houses. This approach would be an inefficient way to build new homes as the existing LIHTC is expensive for the homes produced, with much of the credit value going to developers and financing agencies.

President Biden would renew the expanded child tax credit from the 2021 American Rescue Plan Act, which would raise the CTC value from $2,000 to a maximum value of $3,600 while removing work and income requirements. This CTC expansion would have major fiscal costs totaling over $1 trillion over 10 years above the current-policy CTC. If we include the underlying CTC expansion from the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act that expires at the end of 2025, the cost approaches $2 trillion over 10 years.

In addition to the CTC expansion, the president would expand the EITC and make permanent the expanded Affordable Care Act (ACA) premium tax credits that are scheduled to expire at the end of 2025.

President Biden also committed to preserving and extending the additional funding appropriated to the IRS as part of the Inflation Reduction Act. Biden argues this would help raise revenue from higher earners who evade taxes and would also improve taxpayer services. Much of this new revenue may take time to appear as the IRS trains new staff and spends time identifying evasion and enforcing the tax law. However, the other components of Biden’s tax plan will push the code in a more complex direction, making the job of the IRS to enforce the law more difficult.

Finally, the president recommitted to not raising taxes on people earning under $400,000, arguing that he would fully pay for expiring TCJA individual tax changes with “additional reforms” that would further raise taxes on high earners and businesses. The unspecified reforms would need to total at least $1.4 trillion to cover TCJA extension for people earning under $400,000.

Conclusion

The president’s tax policy proposals as outlined in the State of the Union address would make the tax code more complicated, unstable, and anti-growth, while also expanding the amount of spending in the tax code for a variety of policy goals not related to revenue collection.

We estimate the proposed budget would reduce deficits by $1.4 trillion on a dynamic basis through 2034 compared to the White House estimate of $3.2 trillion. However, neither estimate includes the cost of the intended extension of the TCJA tax cuts for people earning less than $400,000 or for the proposed expanded CTC post-2025, which would wipe out most of the touted deficit reduction.

The budget also assumes an unrealistically high rate of growth in the economy, especially considering the large tax increases proposed on businesses and high earners that will slow growth. The budget assumes real GDP will grow at 2.2 percent annually in the last five years of the budget window, while the CBO assumes real GDP will grow about 1.9 percent annually over this period. By raising marginal tax rates on investment, saving, and work, we find Biden’s FY 2025 budget would reduce long-run economic output by 2.2 percent, wages by 1.6 percent, and employment by 788,000 full-time equivalent jobs.

In sum, President Biden is proposing extraordinarily large tax hikes on businesses and the top 1 percent of earners that would put the U.S. in a distinctly uncompetitive international position and threaten the health of the U.S. economy. The budget ignores or makes unrealistic assumptions about the fiscal cost of major proposals as well as economic growth under higher marginal tax rates on work and investment, concealing what is likely to be a substantial cost borne by American workers and taxpayers.

Stay informed on the tax policies impacting you.

Subscribe to get insights from our trusted experts delivered straight to your inbox.

SUBSCRIBEModeling Notes

We use the Tax Foundation General Equilibrium Tax Model to estimate the impact of tax policies, including recent updates allowing detailed modeling of U.S. multinational enterprises. The model produces conventional and dynamic revenue and distributional estimates of tax policy. Conventional estimates hold the size of the economy constant and attempt to estimate potential behavioral effects of tax policy. Dynamic revenue estimates consider both behavioral and macroeconomic effects of tax policy on revenue. The model also produces estimates of how policies impact measures of economic performance such as GDP, GNP, wages, employment, capital stock, investment, consumption, saving, and the trade deficit.

Note, however, our conventional and dynamic estimates for the stock buyback tax do not account for behavioral shifting from buybacks to dividends, which would also shift the individual income tax base from capital gains to dividends.

Regarding the budget’s proposed changes to the GILTI regime, we modeled most of the major changes including the 75 percent GILTI inclusion rate, country-by-country application, the reduction in the foreign tax credit (FTC) haircut to 5 percent, elimination of the qualified business asset investment (QBAI) exemption, and elimination of the FOGEI exclusion. We did not model the changes allowing carryforward of GILTI FTCs and losses, repeal of the high-tax exemption for subpart F, or the tax increases on dual capacity taxpayers.