Who, you might reasonably ask, was “Atayataghronghta”? I had never heard that Native American name in my many years of historical reading and research centered around our Revolutionary War period, but I had once come across his English name a long time ago: Joseph Louis Cook (c. 1737-1814), also called Colonel Louis Cook in historical records. It wasn’t until I read his life story in my wife’s D.A.R. magazine: American Spirit, November/December 2021 Issue (Vol. 155, #6), in an article by Amanda Taylor, titled, “Unwavering Dedication to the Cause”, that I was able to finally put his Indian and his English names together and discover a not unknown, but long underappreciated, American patriot whose “dedication to the cause” of American liberty should be much better known.

In addition to the D.A.R. magazine mentioned above, I also refer you to the blog, “Black Past.org/African-American History”, in an August 3, 2020 article by Euell A. Nielsen titled: Colonel Joseph Louis Cook…, and to an article in Wikipedia (undated and unattributed) titled: Joseph Louis Cook (with extensive reference notations). It will be from these three sources that I will quote freely as I tell Col. Cook’s quite interesting life story that all American patriots should be familiar with.

So who was this Native American warrior who spoke fluent English and French, and who knew General George Washington—this brave man who fought against the English (and against the young George Washington) with the French forces during the French and Indian War (1754-1763), but who later allied himself with Washington’s patriot forces during our War For American Independence? The two men could not have been more different in every respect. Joseph Louis Cook was born in an area of New York now called “Schuylerville” (near Saratoga) c. 1737 to an Abenaki Indian mother and an African father (possibly of French Canadian parentage), who named him “Nia-man-rigounant”, which in English meant “multicolored bird”. When he was around eight years old, in 1745, little Nia-man and his mother were captured by a raiding party of French nationals and Mohawk Indians. One of the French officers wanted to keep little Nia-man as his slave, but the protests of his mother convinced the Mohawk warriors to intercede and kept him out of the clutches of the French.

Eventually the Mohawk raiding party took the boy and his mother with them and returned to their village of Kahnawake, an Iroquois/Mohawk settlement near Montreal, Canada. According to Wikipedia, “(Nia-man) was formally adopted by a Mohawk family and assimilated into the tribe; he grew up learning their culture and language. In the Mohawk language, he was named “Atayataghronghta” (although the Wikipedia article claims it was spelled “Akiatonharonkwen”) translated as ‘he unhangs himself from the group’.” Obviously, after his adoption into the Mohawk tribe he was raised beside their own children, learned their language, their culture, and even learned to speak English from the Jesuit Catholic missionaries who lived with the Mohawk people.

After his mother died, a Jesuit missionary persuaded the boy to come and live with him and work as his attendant. He gave the boy the name of Joseph Louis Cook, taught him the faith of the Roman Catholic Church, and improved his French language skills. Growing into adulthood, Joseph Louis Cook lived in Kahnawake, the Mohawk settlement, until the onset of The French and Indian War in 1754. Cook cast his lot with his adopted Mohawk Nation on the side of the French during that conflict (and against the English). It was during that war that one of Cook’s friends, Eleazer Williams, wrote that Cook was at the battle against the Braddock expedition in 1755 (a military group that included the young George Washington), and served honorably under French General Montcalm at the Battle of Fort Oswego in 1756. That same year Cook was wounded in a firefight with Rogers’ Rangers near Fort Ticonderoga, in upstate New York (a vast wilderness then).

Cook was given the honor of his first command in 1758, at the Battle of Carillon, after which he was given praise by French General Montcalm. He also fought at the Battle of Sainte-Foy (Battle of Quebec) in 1760. After the war’s conclusion (a victory for the British forces) in 1763, Cook married a woman named Marie-Charlotte, and settled in Caughnawaga, an Indian village in New York. He never totally accepted the British victory over the French and Native American tribes allied with them, and found it unacceptable that his New York homeland was being increasingly settled by large numbers of American colonists. Eventually Cook moved with his family to a Mohawk village called Akwesasne, on the banks of the St. Lawrence River in what was then Quebec. And there he lived, raising his family, until the start of hostilities between the English colonists and the British Crown.

Thus begins the “second half” of this intriguing tale of bravery and dedication, for on an August afternoon in 1775, according to Amanda Taylor, “a tall, broad-shouldered Indian man arrived at (Continental) Army headquarters in Cambridge, Massachusetts. He was introduced to General George Washington as Colonel Louis, Chief of the Caughnawaga. The warrior, who spoke fluent English, advised (Washington) that many Indians and Canadians supported the Colonists’ rebellion against the Crown. He then asked for permission to raise a company of Oneida and Tuscarora warriors.” It’s been recorded in history that General Washington was pleased that many of the Native American people supported the cause of freedom, but was “skeptical” that Congress would approve the funds. (Cook tried at least twice to get Washington’s permission to raise a fighting force, and was eventually successful.)

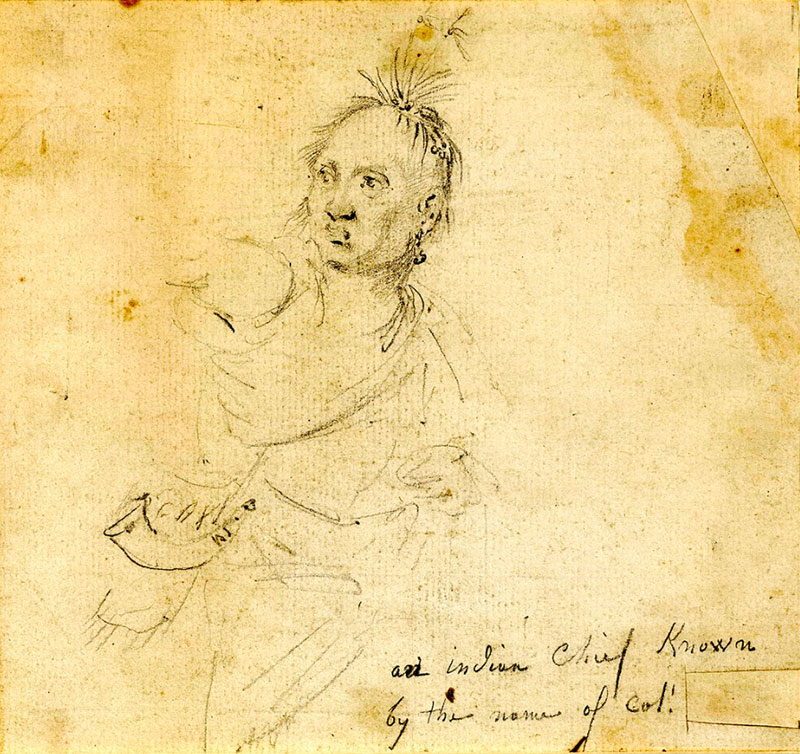

In the early days of our Revolutionary War, Colonel Louis Cook went north and volunteered to be a messenger for American Brigadier General Richard Montgomery during the disaster of the failed American invasion of Quebec (from June, 1775 to October, 1776). General Montgomery was killed during the vicious fighting revolving around the siege of Quebec City, on December 31, 1775. The famous American artist, John Trumbull, included Colonel Louis Cook in his historical painting from 1786 titled: The Death of General Montgomery in the Attack on Quebec, December 31, 1775, a portion of which I’ve included below. You can see the valiant Mohawk warrior, Colonel Louis Cook, wielding his tomahawk in defense of his fellow Americans. Despite a disastrous outcome of this long and bloody campaign, Louis Cook stayed with his fellow American soldiers, and as Captain James Wilkinson would write later: “(Cook was) the only Canadian who accompanied the army in its retreat from Canada.”

Although many of the Native People’s nations allied themselves with the British Crown during the Revolution, hoping that this would result in the expulsion of British/American colonists from their lands, Louis Cook remained faithful to the forces of the British American colonists, as did the Oneida and Tuscarora Nations. During this War of the Revolution, according to Wikipedia: “In New York, Louis Cook was present at the Battle of Oriskany (called the “bloodiest battle of the Revolution—whl), and participated in the Saratoga Campaign (where he was put in command of a company of 150 Indian Rangers—whl)…. Cook was with the Continental Army at Valley Forge in the winter of 1777/78. In Spring, 1778, Peter DuPonceau wrote of meeting Cook, dressed in American regimentals, after hearing (Cook) singing a French aria. In March, 1778, General Philip Schuyler sent Cook to destroy British ships at Niagara in order to prevent another Canadian expedition.”

Joseph Louis Cook finally received his commission as a Lieutenant Colonel in the Continental Army from the Continental Congress on June 15, 1779, a notable achievement at the time, for it was the highest rank ever awarded to an American Indian during the Revolutionary War! It was also the only known commission given to a man of African descent at that time. At this same time, twelve of his fellow Oneida and Tuscarora chiefs also received military commissions from the Continental Congress. All of these men vowed to support the Americans, even if it cost them their lives—which for some of them, it did!

Amanda Taylor tells of the last years of Louis Cook’s life, writing that, “After the American Revolution, Col. Louis moved to an Oneida village, and married (his second wife), Marguerite Thewanihatta. He had three sons and several daughters and went on to serve the United States as a peace negotiator among the various tribes of the Ohio River Valley. Although advanced in age, Col. Louis insisted on fighting with his sons during the War of 1812. On July 25, 1814, during the Battle of Lundy’s Lane, he was injured by a fall from his horse. Days later, in failing health, he asked to be carried back to the Indian settlements near the American camp. His last words were ones of faith, love for his family and tribe, UNDYING LOYALTY TO THE AMERICAN CAUSE (emphasis mine-whl). He died in October, 1814 and was buried near Buffalo, New York.”

I tried to locate a photo of Colonel Cook’s grave, but none seems to exist in the public realm. The tale of this man’s bravery and dedication to causes that risked his life is but one of countless true stories of the patriotic men and women who did a little or a lot to bring lasting liberty to the people of what would become the United States. Yet today those of us who try to be “watchmen on the wall” and warn our fellow citizens of potentially catastrophic political trends are ignored or accused of spreading “conspiracy theories” by those who have sold their souls to the playing or watching of professional sports and by the mouth breathing mediocrities of “wokeness” who love to pretend that the only dangers facing our nation are those revolving around our unwillingness to agree with them that “men can become women and women can become men”, and that there are multiple “genders”, not just two. I wonder what Col. Louis Cook would have thought of that insanity?