Why the Cherokees Sided with the Southern Cause

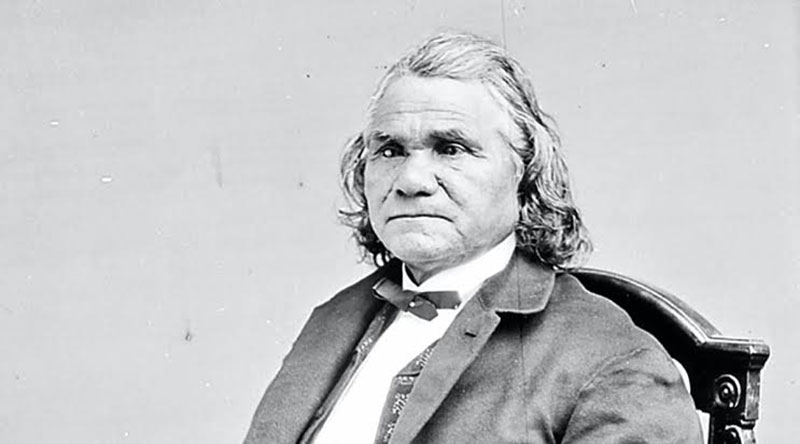

Stand Watie, Brigadier General, CSA, Western Cherokee Principal Chief 1862-1866.

On August 21,1861, the (Western) Cherokee Nation by a General Convention at Tahlequah (in Oklahoma) declared its common cause with the Confederate States against the Northern Union. In separate sympathetic actions their brethren, the Creeks, Seminoles, Choctaws, and Chickasaws joined in this determination. A formal treaty was finalized on October 7, and on October 9, John Ross, the Principal Chief of the Cherokee Nation called into session the Cherokee National Committee and National Council to formally approve and implement the treaty and future course of action.

In 1861, there were two principal groups of Cherokees in the United States, the Western Band with a population slightly over 20,000 and the smaller Eastern Band in North Carolina with a population of only about 2,000. Both sided with the Southern Confederacy, but the larger Western Band made a formal declaration of independence from the United States.

At first, the Western Cherokees had considerable consternation over the growing conflict between the U.S. Government and Southern States. They had much common economy and contact with their Confederate neighbors, but their treaties were with the government of the United States. However, the Northern conduct of the war against their neighbors, strong repression of Northern political dissent, and the roughshod trampling of the U. S Constitution under the new regime and political powers in Washington soon changed their thinking.

At first, the Western Cherokees had considerable consternation over the growing conflict between the U.S. Government and Southern States. They had much common economy and contact with their Confederate neighbors, but their treaties were with the government of the United States. However, the Northern conduct of the war against their neighbors, strong repression of Northern political dissent, and the roughshod trampling of the U. S Constitution under the new regime and political powers in Washington soon changed their thinking.

The Cherokees had come to revere the U.S. Constitution, which was a vital guarantor of their own rights and freedoms under the Federal Government. The Cherokee were also among the best educated, Christianized, and literate of the American Indian tribes. Learning and wisdom were highly esteemed. They were also well aware of and sympathetic to the issues cited in the American Declaration of Independence. Hence the words and framework of the Cherokee Declaration of Independence published on October 28, 1861, bares a strong resemblance to the 1776 U.S. Declaration of Independence. It begins:

A Declaration by the People of the Cherokee Nation of the Causes Which Have Impelled them to Unite Their Fortunes With Those of the Confederate States of America.

“When circumstances beyond their control compel one people to sever the ties which have long existed between them and another state or confederacy, and to contract new alliances and establish new relations for the security of their rights and liberties, it is fit that they should publicly declare the reasons by which their action is justified.”

In the next paragraphs of their declaration the (Western) Cherokee Council noted their faithful adherence to their treaties with the United States in the past and how they had faithfully attempted neutrality until the present. But the seventh paragraph begins to delineate their alarm with Northern aggression and sympathy with the South:

“But Providence rules the destinies of nations, and events, by inexorable necessity, overrule human resolutions.”

Comparing the relatively limited objectives and defensive nature of the Southern cause in contrast to the aggressive actions of the North they remarked of the Confederate States:

“Disclaiming any intention to invade the Northern States, they sought only to repel the invaders from their own soil and to secure the right of governing themselves. They claimed only the privilege asserted in the Declaration of American Independence, and on which the right of Northern States themselves to self-government is formed, and altering their form of government when it became no longer tolerable and establishing new forms for the security of their liberties.”

The next paragraph noted the orderly and democratic process by which each of the Confederate States seceded. This was without violence or coercion and nowhere were liberties abridged or civilian courts and authorities made subordinate to the military. Also noted was the growing unity and success of the South against Northern aggression. The following or ninth paragraph contrasts this with ruthless and totalitarian trends in the North, beginning with Lincoln’s unconstitutional suppression of free speech and even the arrest of Maryland State legislators possibly sympathetic to secession.

“But in the Northern States the Cherokee people saw with alarm a violated constitution, all civil liberty put in peril, and all rules of civilized warfare and the dictates of common humanity and decency unhesitatingly disregarded. In the states which still adhered to the Union, a military despotism had displaced civilian power, and the laws became silent with arms. Free speech and almost free thought became a crime. The right of habeas corpus, guaranteed by the constitution, disappeared at the nod of a Secretary of State or a general of the lowest grade. The mandate of the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court was at naught by the military power and this outrage on common right approved by a President sworn to support the constitution. War on the largest scale was waged, and the immense bodies of troops called into the field in the absence of any warranting it under the pretense of suppressing unlawful combination of men.”

The tenth paragraph continues the indictment of the Northern political party in power and the conduct of the Union Armies:

“The humanities of war, which even barbarians respect, were no longer thought worthy to be observed. Foreign mercenaries and the scum of the cities and the inmates of prisons were enlisted and organized into brigades and sent into Southern States to aid in subjugating a people struggling for freedom, to burn, to plunder, and to commit the basest of outrages on the women; while the heels of armed tyranny trod upon the necks of Maryland and Missouri, and men of the highest character and position were incarcerated upon suspicion without process of law, in jails, forts, and prison ships, and even women were imprisoned by the arbitrary order of a President and Cabinet Ministers, while the press ceased to be free, and the publication of newspapers was suspended and their issues seize and destroyed; the officers and men taken prisoners in the battles were allowed to remain in captivity by the refusal of the Government to consent to an exchange of prisoners as they had left their dead on more than one field of battle that had witnessed their defeat, to be buried and their wounded to be cared for by southern hands.”

The eleventh paragraph of the Cherokee declaration isa fairly concise summary of their grievances against the political powers now presiding over a new U. S. Government:

“Whatever causes the Cherokee people may have had in the past to complain of some of the southern states, they cannot but feel that their interests and destiny are inseparably connected to those of the south. The war now waging is a war of Northern cupidity and fanaticism against the institution of African servitude; against the commercial freedom of the south, and against the political freedom of the states, and its objects are to annihilate the sovereignty of those states and utterly change the nature of the general government.”

The Cherokees felt they had been faithful and loyal to their treaties with the United States, but now perceived that the relationship was not reciprocal and that their very existence as a people was threatened. They had also witnessed the recent exploitation of the properties and rights of Indian tribes in Kansas, Nebraska, and Oregon, and feared that they, too, might soon become victims of Northern rapacity. Therefore, they were compelled to abrogate those treaties in defense of their people, lands, and rights. They felt the Union had already made war on them by their actions.

Finally, appealing to their inalienable right to self-defense and self-determination as a free people, they concluded their declaration with the following words:

“Obeying the dictates of prudence and providing for the general safety and welfare, confident of the rectitude of their intentions and true to their obligations to duty and honor, they accept the issue thus forced upon them, unite their fortunes now and forever with the Confederate States, and take up arms for the common cause, and with entire confidence of the justice of that cause and with a firm reliance upon Devine Providence, will resolutely abide the consequences.”

The Eastern Band of Cherokee made no formal declaration, but considered themselves North Carolinians and were anxious to join Confederate forces in defending their state and the Southern cause. Col. William H. Thomas, a North Carolina State Senator, gathered 416 Cherokee braves to form the core of what later became the Thomas Legion consisting of the Cherokee core and about 1,900 North Carolina mountain men. Thomas, of Welsh descent, was the adopted white son of the late Eastern Band Chief, Yanaguska (Drowning Bear). It should be noted that the 416 Cherokee braves that served in the Thomas Legion represented almost every male of military age of their small population. They served very faithfully with only about a dozen known to have deserted.

The last shot fired in the war east of the Mississippi was May 6, 1865. This engagement was at White Sulphur Springs, near Waynesville, North Carolina, in which Thomas Legion Cherokees and mountain men fought off George Kirk’s Union raiders that had wreaked a murderous terrorism and destruction on the civilian population of Western North Carolina. It took Thomas some effort to persuade his Cherokee braves to surrender rather than continuing guerilla warfare against the Union.

In the West, Cherokee Confederate Brigadier General Stand Watie’s mounted infantry regiments became a legend for their guerilla cavalry tactics, baffling and diverting far greater numbers of Union troops. On June 23, 1865, in what was the last land battle of the war, Confederate Brigadier General and Cherokee Chief, Stand Watie, finally surrendered his predominantly Cherokee, Oklahoma Indian force to the Union.

The Cherokee Declaration of October 28, 1861, uncovers a far more complex set of Civil War issues than most Americans have been taught. However, rediscovered truth is not always welcome. Indeed, some of the issues here are so distressing to those who hold the standard false narrative of the Civil War that the general academic, media, and public reaction has been to rebury truth and shout it down as politically unacceptable.

The notion that slavery was the only real or even principal cause of the Civil War is widely held, but historically ignorant. It has served, however, as a convenient, although truth-deficient justification for the war and its conduct. More recently, it has become a vessel for dishonest and manipulative political virtue-signaling.

Those who ignore the wisdom found in history and forsake truth for political expediency will inherit tyranny, want, and depravity. Do not many of the concerns expressed in the Cherokee Declaration of Independence awaken us to the growing tyrannies and deteriorating state of reason, moral principle, and just law in our present Federal Government and its bureaucracies? Without wisdom, courage, and action, our virtues and liberties will disappear into a nightmarish swamp.

Mike Scruggs is the author of two books: The Un-Civil War: Shattering the Historical Myths; and Lessons from the Vietnam War: Truths the Media Never Told You, and over 600 articles on military history, national security, intelligent design, genealogical genetics, immigration, current political affairs, Islam, and the Middle East.

Mike Scruggs is the author of two books: The Un-Civil War: Shattering the Historical Myths; and Lessons from the Vietnam War: Truths the Media Never Told You, and over 600 articles on military history, national security, intelligent design, genealogical genetics, immigration, current political affairs, Islam, and the Middle East.